Nocardia

| Nocardia | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

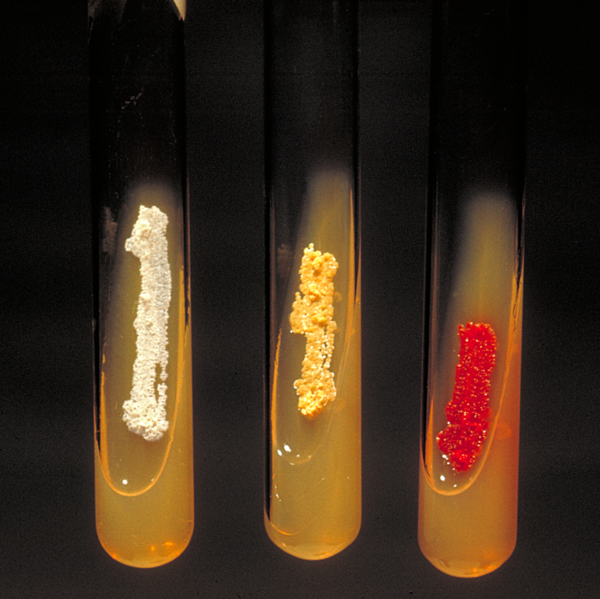

Nocardia asteroides (yellow colonies).

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Nocardia is a genus of Gram-positive, catalase-positive, rod-shaped bacteria; some species are pathogenic (nocardiosis).[1] Nocardia are found worldwide in soil that is rich with organic matter. Most Nocardia infections are acquired by inhalation of the bacteria or through traumatic introduction.

Culture and staining

Nocardia colonies have a variable appearance, but most species appear to have aerial hyphae when viewed with a dissecting microscope, particularly when they have been grown on nutritionally-limiting media. Nocardia grow slowly on non-selective culture media, and are strict aerobes with the ability to grow in a wide temperature range. Some species are partially acid fast due to the presence of intermediate-length mycolic acids in their cell wall.

Virulence

The various species of Nocardia are pathogenic bacteria with low virulence; therefore clinically significant disease most frequently occurs as an opportunistic infection in those with a weak immune system, such as small children, the elderly, and the immunocompromised. Nocardial virulence factors are the enzymes catalase and superoxide dismutase (which inactive reactive oxygen species that would otherwise prove toxic to the bacteria), as well as a "cord factor" (which interferes with phagocytosis by macrophages by preventing the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome).

Clinical disease

Nocardia asteroides is the species of Nocardia most frequently infecting humans, and most cases occur as an opportunistic infection in immunocompromised patents.

The most common form of human nocardial disease is a slowly progressive pneumonia, whose common symptoms include cough, dyspnoea (shortness of breath), and fever. It is not uncommon for this infection to spread to the pleura. Pre-existing pulmonary disease, especially pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, increases the risk of contracting a Nocardia pneumonia.

Nocardia may also cause a variety of cutaneous infections such as actinomycetoma (especially Nocardia brasiliensis), lymphocutaneous disease, cellulitis and subcutaneous abscesses.

About 33% of people with Nocardia infection, this will take the form of encephalitis and/or cerebral abscess formation.

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy with a sulfonamide is the treatment of choice. The most common sulfonamide used is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. People who take trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for other reasons, such as prevention of pneumocystis jiroveci infection in AIDS, have fewer nocardia infections. High-dose imipenem and amikacin have also been used in refractory cases. Antibiotic therapy may have to be continued for six months to a year. Proper wound care is also critical.

Antimicrobial regimen

- 1. Sulfonamide-based therapies [2]

- 1.1 Pulmonary

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMX 10 mg/kg/day (TMP) in 2-4 divided doses IV for 3-6 weeks THEN 2 DS PO bid for at least 5 months

- 1.2 Pulmonary alternatives

- Preferred regimen: Sulfisoxazole OR Sulfadiazine OR Trisulfapyrimidine 3-6 g/day in 2-4 divided doses PO OR TMP-SMX 2 DS bid up to 2 DS tid

- 1.3 CNS (AIDS, severe or disseminated disease)

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMX 15 mg/kg/day (TMP) IV for 3-6 weeks THEN 3 DS PO bid for 6-12 months

- 1.4 CNS alternatives

- Preferred regimen: Imipenem 1000 mg IV q8h OR Ceftriaxone 2 g IV q12h OR Cefotaxime 2-3 g IV q6h AND Amikacin

- 1.5 Severe disease, compromised host, multiple sites

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMX 15 mg/kg/day (TMP) IV AND Amikacin 7.5 mg/kg q12h OR Sulfonamide 6-12 mg/day PO

- 1.6 Sporotrichoid (cutaneous)

- Preferred regimen: TMP-SMX 1 DS bid for 4-6 months

- Note (1): Immunocompetent medicine use for 6 months; Immunosuppressed medicine for 12 months

- Note (2): Treat based on host, site of disease and in vitro activity; Sulfonamide usually preferred, must treat for 6-12 months; Preferred drugs for resistant strains are Amikacin and/or Imipenem

- Note (3): Seriously ill usually treated with IV Imipenem or Sulfonamide or Cefotaxime all potentially combined with Amikacin; less seriously ill treated with oral agents— especially TMP-SMX or Minocycline

- 2. Sulfonamide alternatives

- 2.1 Severe

- Preferred regimen (1): (For AIDS) (Imipenem 1000 mg IV q8h OR Meropenem 2 g q8h AND Amikacin 7.5 mg/kg q12h IV

- Preferred regimen (2): Cefotaxime 2-3 g q6-8h OR Ceftriaxone 2 g/day IV ± Amikacin

- 2.2 Mild

- Preferred regimen: Minocycline 100 mg bid for at least 6 months (initial treatment of local disease or maintenance)

- Alternative regimen: Amoxicillin clavulanate 875/125 mg bid OR Doxycycline OR Erythromycin OR Clarithromycin OR Linezolid OR Fluoroquinolone OR combinations for at least 6 months

Genetics

Despite that Nocardia has interesting and important features such as production of antibiotics and aromatic compound-degrading or converting enzymes, the genetic study of this organism has been hampered by the lack of genetic tools. However, practical Nocardia–E. coli shuttle vectors have been developed recently.[3]

References

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. pp. 460&ndash, 2. ISBN 0838585299.

- ↑ Bartlett, John (2012). Johns Hopkins ABX guide : diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning. ISBN 978-1449625580.

- ↑ Chiba K, Hoshino Y, Ishino K, Kogure T, Mikami Y, Uehara Y, Ishikawa J (2007). "Construction of a Pair of Practical Nocardia-Escherichia coli Shuttle Vectors". Jpn J Infect Dis. 60 (1): 45–7. PMID 17314425.

Further reading

- Ishikawa J, Yamashita A, Mikami Y, Hoshino Y, Kurita H, Hotta K, Shiba T, Hattori M (2004). "The complete genomic sequence of Nocardia farcinica IFM 10152". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101 (41): 14925–30. PMID 15466710.

- Arceneaux, Jean. "Corynebacterium and Related Genera." Lecture to 2nd Year Medical Students at University of Mississippi Medical Center. 10/04/05.

- Greenwood, David, Richard C.B. Slack, and John F. Peutherer. Medical Microbiology: A Guide to Microbial Infections, 16th ed. (2002). ISBN 0-443-07077-6