Ixodes scapularis

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;"|Ixodes scapularis | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| style="background:#Template:Taxobox colour;" | Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ixodes scapularis |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Ixodes scapularis is commonly known as the deer tick or blacklegged tick (although some people reserve the latter term for Ixodes pacificus, which is found on the West Coast of the USA), and in some parts of the USA as the bear tick.[1] It is a hard-bodied tick (family Ixodidae) of the eastern and northern Midwestern United States. It is a vector for several diseases of animals, including humans (Lyme disease, babesiosis, anaplasmosis, Powassan virus disease, etc.) and is known as the deer tick owing to its habit of parasitizing the white-tailed deer. It is also known to parasitize mice,[2] lizards,[3] migratory birds,[4] etc. especially while the tick is in the larva or nymph stage.

Description

- When the deer tick has consumed a blood meal its abdomen will be a light grayish-blue color, whereas the tick itself is chiefly black.

- In identifying an engorged tick it is helpful to concentrate on the legs and upper part of the body

- Most images of Ixodes scapularis that are commonly available—show an adult that is unengorged, that is, an adult that has not had a blood meal.

- Ticks are generally removed immediately upon discovery to minimize the chance of disease.

- However, the abdomen that holds blood is so much larger when engorged and looks so different from the rest of the tick that it would be easy to assume that an engorged specimen of Ixodes scapularis is an entirely different tick (see photo below).

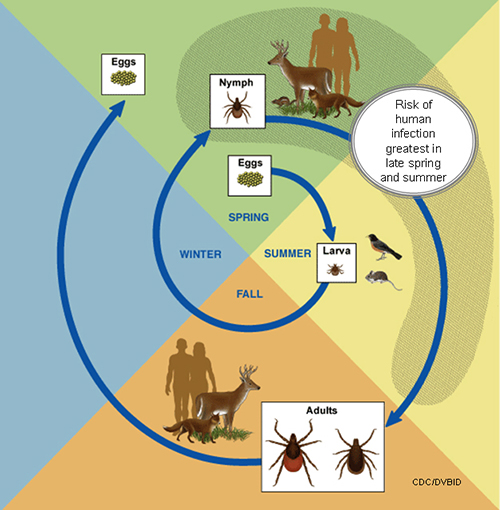

Life Cycle

General Tick Life Cycle

- A tick's life cycle is composed of four stages: hatching (egg), nymph (six legged), nymph (eight legged), and an adult.

- Ticks require blood meal to survive through their life cycle.

- Hosts for tick blood meals include mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. Ticks will most likely transfer between different hosts during the different stages of their life cycle.

- Humans are most often targeted during the nymph and adult stages of the life cycle.

- Life cycle is also dependent on seasonal variation.

- Ticks will go from eggs to larva during the summer months, infecting bird or rodent host during the larval stage.

- Larva will infect the host from the summer until the following spring, at which point they will progress into the nymph stage.

- During the nymph stage, a tick will most likely seek a mammal host (including humans).

- A nymph will remain with the selected host until the following fall at which point it will progress into an adult.

- As an adult, a tick will feed on a mammalian host. However unlike previous stages, ticks will prefer larger mammals over rodents.

- The average tick life cycle requires three years for completion.

- Different species will undergo certain variations within their individual life cycles. [5]

Spread of Tick-borne Disease

- Ticks require blood meals in order to progress through their life cycles.

- The average tick requires 10 minutes to 2 hours when preparing a blood meal.

- Once feeding, releases anesthetic properties into its host, via its saliva.

- A feeding tube enters the host followed by an adhesive-like substance, attaching the tick to the host during the blood meal.

- A tick will feed for several days, feeding on the host blood and ingesting the host's pathogens.

- Once feeding is completed, the tick will seek a new host and transfer any pathogens during the next feeding process. [5]

Behavior

- I. scapularis has a two-year life cycle, during which time it passes through three stages: larva, nymph, and adult.

- The tick must take a blood meal at each stage before maturing to the next.

- Deer tick females latch onto a host and drink its blood for four to five days.

- Deer are the preferred host of the deer tick, but it is also known to feed on small rodents.[6]

- After she is engorged, the tick drops off and overwinters in the leaf litter of the forest floor.

- The following spring, the female lays several hundred to a few thousand eggs in clusters.[7]

- Transtadial (between tick stages) passage of Borrelia burgdorferi is common. Vertical passage (from mother to egg) of Borrelia is uncommon.

- I. scapularis may be active even after a moderate to severe frost, as daytime temperatures can warm them enough to keep them actively searching for a host.

- In the spring, they can be one of the first invertebrates to become active.

- Deer ticks can be quite numerous and seemingly gregarious in areas where they are found.

Ixodes scapularis Transmitted Diseases

- Ixodes scapularis is the main vector of Lyme disease in North America.[8] It can also transmit other Borrelia species, including Borrelia miyamotoi.[9]

- Other parasitic organism transmitted by I. scapularis include:

- Theileria microti a parasitic organism responsible for Babesiosis.

- Anaplasma phagocytophilum the bacterial infection responsible for human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA).[10]

- Among early Lyme disease patients, depending on their location, 2%–12% will also have HGA and 2%–40% will have babesiosis.[11]

- Co-infections complicate Lyme symptoms, especially diagnosis and treatment.

- It is possible for a tick to carry and transmit one of the co-infections and not Borrelia, making diagnosis difficult and often elusive.

- The Centers for Disease Control's emerging infectious diseases department did a study in rural New Jersey of 100 ticks, and found 55% of the ticks were infected with at least one of the pathogens.[12]

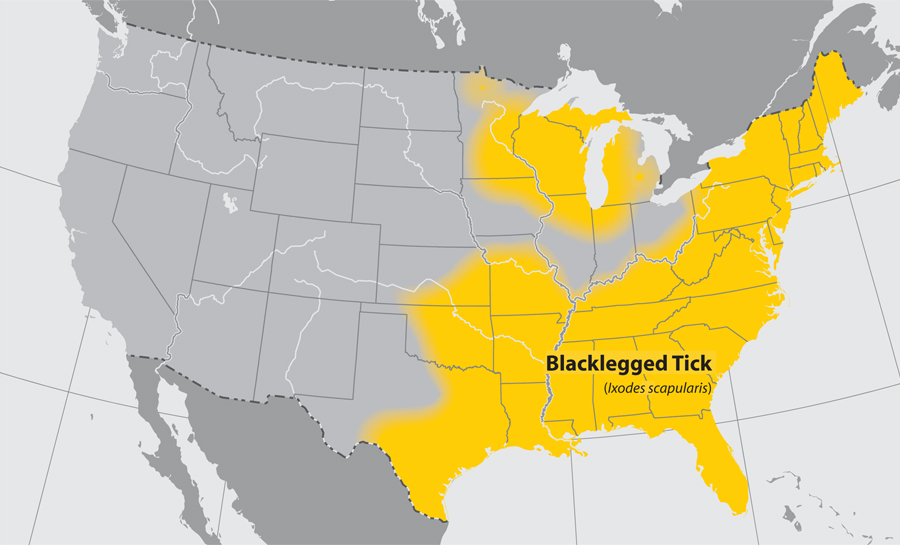

Geographic Distribution

- Northeastern and upper Midwestern United States

Genome sequencing

| NCBI genome ID | 523 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | diploid |

| Genome size | 1,765.38 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 15 pairs |

| Year of completion | 2008 |

- The genome of I. scapularis has been sequenced.[13]

References

- ↑ Drummond, Roger (2004). Ticks and What You Can Do about Them (3rd ed.). Berkeley, California: Wilderness Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-89997-353-1.

- ↑ PMID 7799148 (PMID 7799148)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ PMID 9439111 (PMID 9439111)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2268299/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Life Cycle of Ticks that Bite Humans (2015). http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html Accessed on December 30, 2015

- ↑ "Westport Weston Health District". 2004. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- ↑ Suzuki, David; Grady, Wayne (2004). Tree: A Life Story. Vancouver: Greystone Books. p. 110. ISBN 1-55365-126-X.

- ↑ Brownstein, John S.; Holford, Theodore R.; Fish, Durland (2005). "Effect of Climate Change on Lyme Disease Risk in North America". EcoHealth. 2 (1): 38–46. doi:10.1007/s10393-004-0139-x. PMC 2582486. PMID 19008966.

- ↑ McNeil, Donald (19 September 2011). "New Tick-Borne Disease Is Discovered". The New York Times. pp. D6. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ↑ Steere AC (July 2001). "Lyme disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (2): 115–25. doi:10.1056/NEJM200107123450207. PMID 11450660.

- ↑ G. P. Wormser (June 2006). "Clinical practice. Early Lyme disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (26): 2794–801. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp061181. PMID 16807416.

- ↑ Varde S, Beckley J, Schwartz I (1998). "Prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in Ixodes scapularis in a rural New Jersey County". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (1): 97–99. doi:10.3201/eid0401.980113. PMC 2627663. PMID 9452402.

- ↑ Ixodes scapularis genome sequence at VectorBase

External links

- Information on Tick-Related Health Threats and Deer Tick Fact Sheet from the National Pest Management Association

- blacklegged tick, Ixodes scapularis on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Ixodes scapularis, black-legged tick, deer tick overview as a vector for Lyme disease, developmental stages at MetaPathogen

- Ixodes scapularis genome sequence at VectorBase

- Powassan Virus: Transmission on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

Please read to protect yourself from Deer ticks that may cause Lyme disease. Public Health Fact Sheet: Lyme Disease

Gallery

- Common name: blacklegged tick, deer tick

- Scientific name: Ixodes scapularis

- Reservoir: small mammals and birds (larvae and nymphs); rodents and mammals (adult ticks)

- Geographic distribution: northeastern and upper midwestern United States

- Disease transmitted: anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Lyme disease

-

Approximate distribution of the Blacklegged tick

Adapted from CDC