|

|

| Line 17: |

Line 17: |

|

| |

|

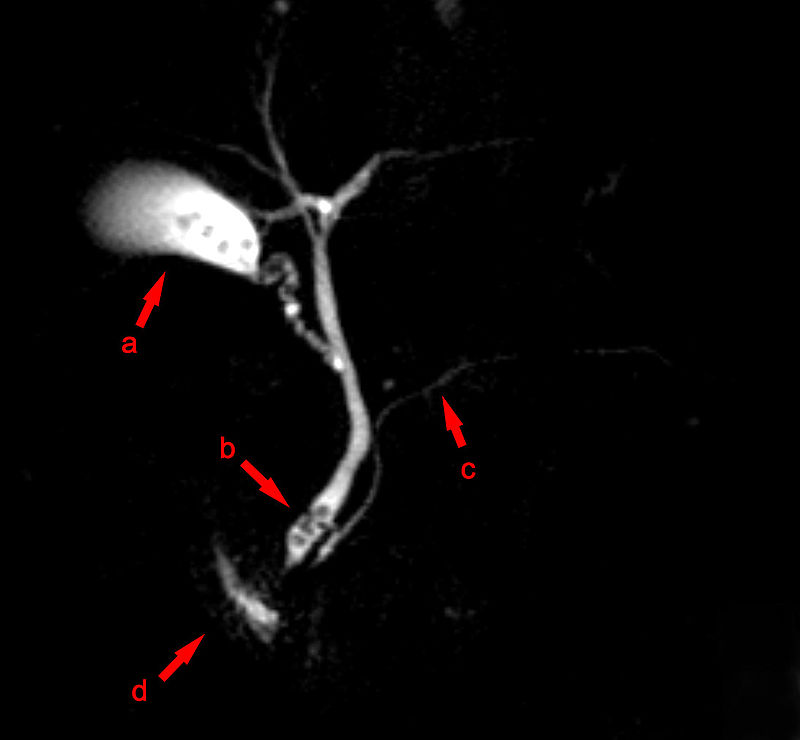

| [[Image:mrcp.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Source:Hellehoff of Wikimedia Commons<ref name="urlMagnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography - Wikipedia">{{cite web |url=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_resonance_cholangiopancreatography#/media/File:MRCP_Choledocholithiasis.jpg |title=Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography - Wikipedia |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> ]] | | [[Image:mrcp.jpg|thumb|center|500px|Source:Hellehoff of Wikimedia Commons<ref name="urlMagnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography - Wikipedia">{{cite web |url=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_resonance_cholangiopancreatography#/media/File:MRCP_Choledocholithiasis.jpg |title=Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography - Wikipedia |format= |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> ]] |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| ====Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)==== Although this is a form of imaging, it is both diagnostic and therapeutic, and is often classified with surgeries rather than with imaging.

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreaticogram (ERCP)

| |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticogram (ERCP) is often performed by gastroenterologists or surgeons, and not by radiologists. This test involves putting a tube into the patient's mouth, down the throat, into the stomach, through the duodenum and then, into the common bile duct. ERCP is performed with the patient sedated.

| |

| Looking through the tube, the gastroenterologist is able to locate the hole in the duodenum where the bile comes in from the common bile duct. A smaller tube or catheter is passed through this hole and contrast material is injected. The contrast agent (dye) also can be injected into the pancreatic duct, showing that ductal system as well.

| |

| The thick endoscopic tube affords visualization and other things as well. If the problem is a stone in the lower bile duct, the gastroenterologist can often put a basket into the tube and snare the stone and remove it. If the problem is tumor, the endoscopist can insert a biopsy device and remove a small piece of tissue for review by the pathologist.

| |

| Finally, the endoscopist can help open the connection between the common bile duct and the duodenum by cutting the muscle that encircles the valve (sphincterotomy)—allowing stones that would have been trapped at the junction to flow right on through.

| |

|

| |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography — Traditionally, ERCP (image 2) was used both as a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure in patients with suspected choledocholithiasis. The sensitivity of ERCP for choledocholithiasis is estimated to be 80 to 93 percent, with a specificity of 99 to 100 percent [28,29]. However, ERCP is invasive, requires technical expertise, and is associated with complications such as pancreatitis, bleeding, and perforation. As a result, ERCP is now reserved for patients who are at high risk for having a common bile duct stone, particularly if there if evidence of cholangitis, or who have had a stone demonstrated on other imaging modalities. (See 'High-risk patients' above and "Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: Indications, patient preparation, and complications".)

| |

|

| |

| EUS and MRCP — EUS (image 3) and MRCP (picture 1) have largely replaced ERCP for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis in patients at intermediate risk for choledocholithiasis. EUS is less invasive than ERCP, and MRCP is noninvasive. Both tests are highly sensitive and specific for choledocholithiasis [30]. Deciding which test should be performed first depends on various factors such as ease of availability, cost, patient-related factors, and the suspicion for a small stone (table 1). (See 'Intermediate-risk patients' above and "Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography" and "Endoscopic ultrasound in patients with suspected choledocholithiasis".)

| |

|

| |

| EUS and MRCP for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis have been evaluated using ERCP as the reference standard:

| |

|

| |

| ●A meta-analysis of 27 studies with 2673 patients found that EUS had a sensitivity of 94 percent and a specificity of 95 percent [31].

| |

| ●A review of 13 studies found that MRCP had a median sensitivity of 93 percent and a median specificity of 94 percent [32].

| |

| Studies have prospectively compared the accuracy of EUS with MRCP in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. These have been reviewed in two systemic reviews, both of which showed no significant differences between the two modalities [33,34]. In a pooled analysis of 301 patients from five randomized trials that compared EUS with MRCP, there was no statistically significant difference in aggregated sensitivity (93 versus 85 percent) or specificity (96 versus 93 percent).

| |

|

| |

| MRCP is preferred for many patients because it is noninvasive. However, the sensitivity of MRCP may be lower for small stones (<6 mm, (image 3)) [35], and biliary sludge can be detected by EUS, but generally not by MRCP. As a result, EUS should be considered in patients in whom the suspicion for choledocholithiasis remains moderate to high despite a negative MRCP. (See 'Intermediate-risk patients' above.)

| |

|

| |

| Intraoperative cholangiography — Intraoperative cholangiography has an estimated sensitivity of 59 to 100 percent for diagnosing choledocholithiasis, with a specificity of 93 to 100 percent [29,36,37]. However, it is highly operator-dependent and is not routinely performed by many surgeons [38].

| |

|

| |

| In the era prior to laparoscopic surgery, patients with gallstone disease and suspected choledocholithiasis underwent open cholecystectomy including cholangiography and palpation of the common bile duct and/or open exploration of the common bile duct to diagnose and treat choledocholithiasis. As laparoscopic surgery replaced open surgery as the preferred method for cholecystectomy, exploration of the common bile duct for removal of intraductal stones became technically more challenging. (See "Laparoscopic cholecystectomy", section on 'Evaluation for choledocholithiasis' and "Common bile duct exploration", section on 'Intraoperative cholangiography'.)

| |

|

| |

| With improvements in cholangiography techniques and the use of fluoroscopic rather than static cholangiography, the successful completion rate and accuracy of intraoperative cholangiography have improved over time [39]. In practice, the use of intraoperative cholangiography is highly operator-dependent and may be technically unfeasible in patients with a severely inflamed gallbladder or with a tiny or inflamed cystic duct.

| |

|

| |

| Studies of intraoperative cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy have shown the following:

| |

|

| |

| ●In a review of 13 studies with 1980 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 9 percent had choledocholithiasis [36]. The success rate for technical completion of intraoperative cholangiography ranged from 88 to 100 percent. Intraoperative cholangiography had a sensitivity of 68 to 100 percent and a specificity of 92 to 100 percent for diagnosing choledocholithiasis.

| |

| ●In a more recent prospective population-based study, intraoperative cholangiography was routinely attempted in 1171 patients undergoing cholecystectomy [37]. The cholecystectomy was carried out laparoscopically in 79 percent. Intraoperative cholangiography was successful in 95 percent, and choledocholithiasis was identified in 134 patients (11 percent). The sensitivity and specificity of intraoperative cholangiography were 97 and 99 percent, respectively.

| |

| There is ongoing debate about the routine use of intraoperative cholangiography in all patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus selective use in patients at increased risk for intraductal stones, and practices vary widely among surgeons. Proponents of routine intraoperative cholangiography argue that it permits delineation of biliary anatomy, reduces and identifies bile duct injuries, and identifies asymptomatic choledocholithiasis. Opponents argue that intraoperative cholangiography adds to procedure time and expense. In addition, they argue that asymptomatic common bile duct stones may pass spontaneously and/or have a low potential for causing complications, such that their identification may lead to unnecessary common bile duct exploration and/or conversion to open surgery [40-50].

| |

|

| |

| A 2008 study examined the frequency with which surgeons employ intraoperative cholangiography. In the survey of 1417 surgeons, 27 percent defined themselves as routine intraoperative cholangiography users [38]. Among the routine users, 91 percent reported using intraoperative cholangiography in more than 75 percent of laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Academic surgeons were less often routine users compared with nonacademic surgeons (15 versus 30 percent).

| |

|

| |

|

| ==References== | | ==References== |