Ectopic pregnancy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}} | }} | ||

{{Search infobox}} | {{Search infobox}} | ||

{{SZ}} | |||

{{Editor Help}} | {{Editor Help}} | ||

Revision as of 18:40, 26 March 2009

| Ectopic pregnancy | |

| |

|---|---|

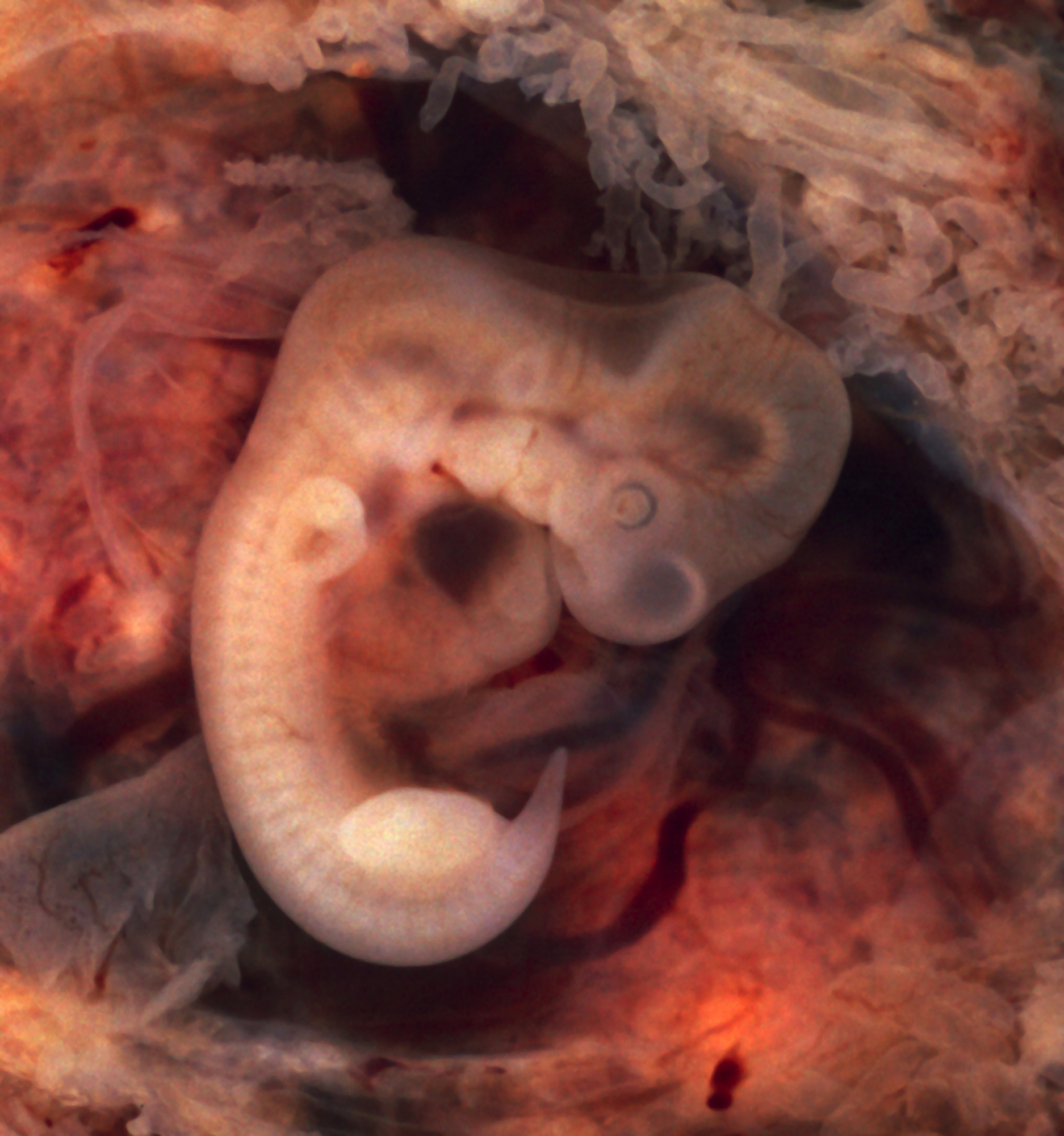

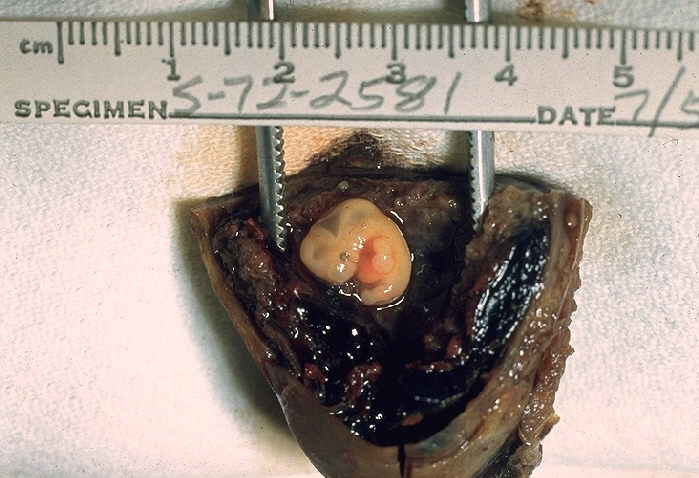

| Oviduct with an ectopic pregnancy (tubal pregnancy) | |

| ICD-10 | O00 |

| ICD-9 | 633 |

| DiseasesDB | 4089 |

| MedlinePlus | 000895 |

| eMedicine | med/3212 emerg/478 radio/231 |

Template:Search infobox Editor-in-Chief: Stacie Zelman, MD [1]

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [2] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

In a normal pregnancy, the fertilized egg enters the uterus and settles into the uterine lining where it has plenty of room to divide and grow. About 1% of pregnancies are in an ectopic location with implantation not occurring inside of the womb, and of these 98% occur in the Fallopian tubes.[1]

In a typical ectopic pregnancy, the embryo does not reach the uterus, but instead adheres to the lining of the Fallopian tube. The implanted embryo burrows actively into the tubal lining. Most commonly this invades vessels and will cause bleeding. This bleeding expels the implantation out of the tubal end as a tubal abortion. Some women thinking they are having a miscarriage are actually having a tubal abortion. There is no inflammation of the tube in ectopic pregnancy. The pain is caused by prostaglandins released at the implantation site, and by free blood in the peritoneal cavity, which is locally irritant. Sometimes the bleeding might be heavy enough to threaten the health or life of the woman. Usually this degree of bleeding is due to delay in diagnosis, but sometimes, especially if the implantation is in the proximal tube (just before it enters the uterus), it may invade into the nearby Sampson artery, causing heavy bleeding earlier than usual.

If left untreated, about half of ectopic pregnancies will resolve without treatment. These are the tubal abortions. The advent of methotrexate treatment for ectopic pregnancy has reduced the need for surgery; however, surgical intervention is still required in cases where the Fallopian tube has ruptured or is in danger of doing so. This intervention may be laparoscopic or through a larger incision, known as a laparotomy.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) remains one of the few life threatening diseases where the incidence is increasing (19.7 / 1000 pregnancies in 1992) but the mortality is decreasing.

Differential Diagnosis of Ectopic Pregnancy

- Threatened or incomplete abortion

- Adnexal torsion

- Appendicitis

- Ruptured corpus luteum cyst

- Pancreatitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Pyelonephritis

Risk Factors

| Risk Factor | Odds Ratio |

| Tubal surgery | 21 |

| Tubal ligation | 9.3 |

| Previous ectopic | 8.3 |

| In-utero DES exposure | 5.6 |

| IUD | 4.2 – 45 |

| Documented tubal pathology | 3.8 – 21 |

| Moderate Risk | |

| Infertility | 2.5 – 21 |

| Previous STD | 2.5 – 3.7 |

| Multiple sexual partners | 2.1 |

| Low Risk | |

| Prior pelvic / abd surgery | 0.9 – 3.8 |

| Cigarette smoking | 2.3 – 2.5 |

| Vaginal douching | 1.1 – 3.1 |

| 1st intercourse < 18 years old | 1.6 |

- Although tubal ligation prevents pregnancies, if a pregnancy does occur, it is more likely to be ectopic.

- The risk of EP increases in women who have had prior ectopics, but decreases for each subsequent intrauterine pregnancy.

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) causes a loss of fimbriae, a small opening, and fallopian tubes that are shorter and thinner than normal.

- Infertility primarily increases the risk of EP during treatment – IVF (in vitro fertilization) is associated with a 2 – 3 % increased risk compared with the general population.

Causes

There are a number of risk factors for ectopic pregnancies. They include: pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, those who have been exposed to DES, tubal surgery, smoking, previous ectopic pregnancy, multiple sexual partners, current IUD use, tubal ligation, and previous abortion.[2]

Cilial damage and tube occlusion

Hair-like cilia located on the internal surface of the Fallopian tubes carry the fertilized egg to the uterus. Damage to the cilia or blockage of the Fallopian tubes is likely to lead to an ectopic pregnancy. Women with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) have a high occurrence of ectopic pregnancy. This results from the build-up of scar tissue in the Fallopian tubes, causing damage to cilia. If however both tubes were occluded by PID, pregnancy would not occur and this would be protective against ectopic pregnancy. Tubal surgery for damaged tubes might remove this protection and increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy. Tubal ligation can predispose to ectopic pregnancy. Seventy percent of pregnancies after tubal cautery are ectopic, while 70% of pregnancies after tubal clips are intrauterine. Reversal of tubal sterilization (Tubal reversal) carries a risk for ectopic pregnancy. This is higher if more destructive methods of tubal ligation (tubal cautery, partial removal of the tubes) have been used than less destructive methods (tubal clipping). A history of ectopic pregnancy increases the risk of future occurrences to about 10%. This risk is not reduced by removing the affected tube, even if the other tube appears normal. The best method for diagnosing this is to do an early ultrasound.

Association with infertility

Infertility treatments are highly variable and specific to individual patients. In vitro fertilization is used for patients with damaged tubes, which are an inherent risk factor for ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancies have been seen with in vitro fertilization, but this is an uncommon complication and quickly diagnosed by the early ultrasounds that these intensively surveyed patients undergo.

Hysterectomy

Ectopic pregnancy occasionally occurs in women who have had a hysterectomy. Rather than implanting in the absent uterus, the fetus implants in the abdomen, and must be delivered via caesarean section.[3] [3]

Other

Patients are at higher risk for ectopic pregnancy with advancing age. Also, it has been noted that smoking is associated with ectopic risk. Vaginal douching is thought by some to increase ectopic pregnancies; this is speculative. Women exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero (aka "DES Daughters") also have an elevated risk of ectopic pregnancy, up to 3 times the risk of unexposed women.

Diagnosis

Symptoms

- The most common presenting symptoms are amenorrhea and abdominal pain.

- The pain is usually in the lower abdomen, but can be generalized or radiate to the shoulder (especially in ruptured ectopics) and is present in 90% of patients.

- Vaginal bleeding is also common (50 – 80%), and can be difficult to distinguish from spontaneous abortion.

Early symptoms are either absent or subtle. Clinical presentation of ectopic pregnancy occurs at a mean of 7.2 weeks after the last normal menstrual period, with a range of 5 to 8 weeks. Later presentations are more common in communities deprived of modern diagnostic ability.

The early signs are:

- Pain and discomfort, usually mild. A corpus luteum on the ovary in a normal pregnancy may give very similar symptoms.

- Vaginal bleeding, usually mild. An ectopic pregnancy is usually a failing pregnancy and falling levels of progesterone from the corpus luteum on the ovary cause withdrawal bleeding. This can be indistinguishable from an early miscarriage or the 'implantation bleed' of a normal early pregnancy.

- Pain while having a bowel movement

Patients with a late ectopic pregnancy typically have pain and bleeding. This bleeding will be both vaginal and internal and has two discrete pathophysiologic mechanisms.

- External bleeding is due to the falling progesterone levels.

- Internal bleeding is due to hemorrhage from the affected tube.

The differential diagnosis at this point is between miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and early normal pregnancy. The presence of a positive pregnancy test virtually rules out pelvic infection as it is rare indeed to find pregnancy with an active Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID). The most common misdiagnosis assigned to early ectopic pregnancy is PID.

More severe internal bleeding may cause:

- Lower back, abdominal, or pelvic pain.

- Shoulder pain. This is caused by free blood tracking up the abdominal cavity, and is an ominous sign.

- There may be cramping or even tenderness on one side of the pelvis.

- The pain is of recent onset, meaning it must be differentiated from cyclical pelvic pain, and is often getting worse.

- Ectopic pregnancy is noted that it can mimic symptoms of other diseases such as appendicitis, other gastrointestinal disorder, problems of the urinary system, as well as pelvic inflammatory disease and other gynaecologic problems.

Signs

- Abdominal tenderness is present in 90% of patients

- Cervical motion tenderness is present in 67% of patients

- A palpable mass is present in ~ 50% of patients

- Signs of rupture include tachycardia, orthostasis, rebound tenderness and guarding

Diagnostic Studies

Can be made by the 7th week of pregnancy (~ 4.5 weeks after conception).

- The definitive diagnosis is made on laparoscopic inspection of the fallopian tube.

- Algorithms have been developed that reduce the need for surgery, and include serial beta-HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) measurements and transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).

- Although these algorithms are felt to be 97% sensitive and 95% specific, they may delay the diagnosis.

- ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) can detect beta-HCG as low as 1.0 IU/L. In the normal pregnancy this doubles every 2 days, whereas abnormal pregnancies (intrauterine or ectopic) have impaired beta-HCG production and longer doubling times.

- An intrauterine gestation can generally be seen on TVUS when the beta-HCG is > 1500 IU/L (generally ~ 5 – 6 weeks gestation).

- Absence of an intrauterine gestation with beta-HCG concentrations above this level is diagnostic of an EP (100% sensitive and specific).

- The presence of an adnexal mass when the beta-HCG is > 1,000 IU/L has a sensitivity of 97%, a specificity of 99%, and a PPV and NPV of 98%.

- Other algorithms use serum progesterone measurements and / or uterine curettage.

- If the serum progesterone is > 25 ng/ml, EP can be excluded (sensitivity of 97.5%).

- Curettage is done only after a non-viable pregnancy has been confirmed by either a serum progesterone < 5 ng/ml (100% sensitivity) or by the absence of a rise in beta-HCG after 2 days.

- If the progesterone is between 5 and 25 ng/ml a TVUS should be performed.

- A decrease in the beta-HCG of >=15% 8 – 12 hours after curettage is diagnostic of complete abortion. If the beta-HCG does not fall, EP is diagnosed.

- Although these algorithms are felt to be 97% sensitive and 95% specific, they may delay the diagnosis.

Histopathological Findings: Fallopian tube: Ectopic pregnancy with embryo

<youtube v=Hk0AEmW_IGw/>

Treatment

There has only been one randomized controlled trail comparing medical to surgical therapy, and there was no difference as far as elimination of the EP or tubal preservation, however the methotrexate (MTX) group had a higher incidence of side effects.

Nonsurgical treatment

Early treatment of an ectopic pregnancy with the antimetabolite methotrexate has proven to be a viable alternative to surgical treatment[4] since 1933.[5] If administered early in the pregnancy, methotrexate can disrupt the growth of the developing embryo causing the cessation of pregnancy. As actively proliferating trophoblasts have a high rate of de-novo purine and pyrimidine synthesis, they are especially vulnerable to MTX. MTX therapy is generally reserved for EPs < 4cm on ultrasound in stable patients.

- Dosing regimens include:

- Variable dose: MTX 1 mg/kg IM qod, alternating with leucovorin 0.1 mg/kg IM qod. This is continued until the beta-HCG falls >=15% in 48 hours, or 4 doses of MTX have been given.

- Single dose: MTX 50 mg/m2 IM (can be repeated if beta-HCG on day 7 is >=level on day 4). Although more convenient, it has a slightly higher risk of persistent EP.

- Direct injection at the site of implantation has a lower success rate, still requires laparoscopy or ultrasound guidance, and has no benefits consistent with systemic MTX.

- Transient pelvic pain is relatively common with MTX therapy, and it is often difficult to distinguish therapeutic pain from that of a rupturing ectopic.

- Expectant management with watchful waiting works in ~ 68% of patients.

Surgical treatment

About half of ectopics result in tubal abortion and are self limiting. The option to go to surgery is thus often a difficult decision to make in an obviously stable patient with minimal evidence of blood clot on ultrasound.

Surgery is the treatment of choice when there is rupture, hypotension, anemia, pain for > 24 hours, or a gestational sac > 4 cm on ultrasound.

Laparoscopy or laparotomy can be used to gain access to the pelvis and can be used to either incise the affected Fallopian tube and remove only the pregnancy (salpingostomy) or remove the affected tube with the pregnancy (salpingectomy). The first successful surgery for an ectopic pregnancy was performed by Robert Lawson Tait in 1883.[6] Laparoscopy is cheaper and associated with an improved post-op course, however, laparotomy is preferred when there is hemodynamic instability, when the surgeon isn’t familiar with laparoscopy or if the laparoscopic approach is technically too difficult. Linear salpingostomy is recommended for ampullary EPs, whereas segmental excision with microsurgical anastomosis is suggested for isthmic pregnancies. Salpingostomy is successful in 93% of cases, and 76% of patients have patent tubes after the procedure. The most common complication is persistent ectopic tissue, which occurs 5 – 20% of the time. Salpingostomy has been shown to have equivalent rates of subsequent fertility and EP as salpingectomy. Many authors suggest salpingectomy in patients with uncontrollable bleeding, extensive tubal damage, recurrent ectopic in the same tube, and obviously, when the woman requests sterilization.

Chances of future pregnancy

The chance of future pregnancy depends on the status of the adnexa left behind. The chance of recurrent ectopic pregnancy is about 10% and depends on whether the affected tube was repaired (salpingostomy) or removed (salpingectomy). Successful pregnancy rates vary widely between different centries, and appear to be operator dependent. Pregnancy rates with successful methotrexate treatment compare favorably with the highest reported pregnancy rates. Often, patients may have to resort to in vitro fertilisation to achieve a successful pregnancy. The use of in vitro fertilization does not preclude further ectopic pregnancies, but the likelihood is reduced.

Complications

The most common complication is rupture with internal bleeding that leads to shock. Death from rupture is rare in women who have access to modern medical facilities. Infertility occurs in 10 - 15% of women who have had an ectopic pregnancy.

References

- ↑ Serdar Ural (May 2004). "Ectopic pregnancy". KidsHealth. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ↑ "BestBets: Risk Factors for Ectopic Pregnancy".

- ↑ SA Carson, JE Buster, Ectopic Pregnancy. New Engl J Med 329:1174-1181

- ↑ Mahboob U, Mazhar SB (2006). "Management of ectopic pregnancy: a two-year study". Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad : JAMC. 18 (4): 34–7. PMID 17591007.

- ↑ Clark L, Raymond S, Stanger J, Jackel G (1989). "Treatment of ectopic pregnancy with intraamniotic methotrexate--a case report". The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 29 (1): 84–5. PMID 2562613.

- ↑ "eMedicine - Surgical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy : Article Excerpt by R Daniel Braun". Retrieved 2007-09-17.

External links

The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust* [4] - Information and support for those who have suffered the condition by a medically overseen and moderated, UK based charity, recognised by the National Health Service (UK) Department of Health (UK) and The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists * [5]

Acknowledgements

The content on this page was first contributed by: David Feller-Kopman, M.D. and Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [6]

ar:حمل خارج الرحم bs:Vanmaterična trudnoća ca:Embaràs ectòpic de:Extrauteringravidität hr:Ektopična trudnoća id:Kehamilan Ektopik is:Utanlegsfóstur it:Gravidanza ectopica lt:Ektopinis nėštumas nl:Buitenbaarmoederlijke zwangerschap sl:Zunajmaternična nosečnost sr:Ванматерична трудноћа sv:Utomkvedshavandeskap