Concussion: Difference between revisions

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Common causes include sports injuries, bicycle accidents, auto accidents, and falls; the latter two are the most frequent causes among adults.<ref name="pmid17215534"/> Concussion may be caused by a blow to the head, or by [[acceleration]] or deceleration forces without a direct impact. The forces involved disrupt cellular processes in the [[brain]] for days or weeks. | |||

It is not known whether the concussed brain is structurally damaged the way it is in other types of brain injury (albeit to a lesser extent) or whether concussion mainly entails a loss of function with [[physiology|physiological]] but not structural changes.<ref name="Shaw02"> | It is not known whether the concussed brain is structurally damaged the way it is in other types of brain injury (albeit to a lesser extent) or whether concussion mainly entails a loss of function with [[physiology|physiological]] but not structural changes.<ref name="Shaw02"> | ||

Revision as of 14:10, 27 February 2013

For patient information, click here

| Concussion | |

| |

|---|---|

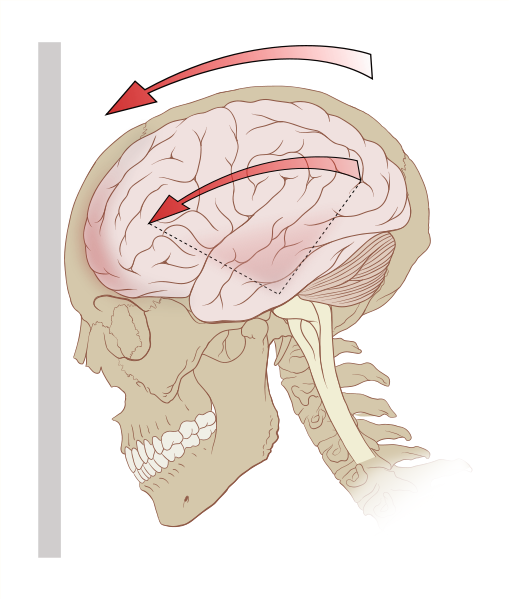

| Deceleration can exert rotational forces in the brain, especially the midbrain and diencephalon. |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

|

Concussion Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Concussion On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Concussion |

Background

Common causes include sports injuries, bicycle accidents, auto accidents, and falls; the latter two are the most frequent causes among adults.[1] Concussion may be caused by a blow to the head, or by acceleration or deceleration forces without a direct impact. The forces involved disrupt cellular processes in the brain for days or weeks.

It is not known whether the concussed brain is structurally damaged the way it is in other types of brain injury (albeit to a lesser extent) or whether concussion mainly entails a loss of function with physiological but not structural changes.[2] Cellular damage has reportedly been found in concussed brains, but it may have been due to artifacts from the studies.[3] A debate about whether structural damage exists in concussion has raged for centuries and is ongoing.

Definitions

No single definition of concussion, mild head injury,[4] or mild traumatic brain injury is universally accepted, though a variety of definitions have been offered.[5] In 2001, the first International Symposium on Concussion in Sport was organized by the International Olympic Committee Medical Commission and other sports federations.[6] A group of experts called the Concussion in Sport Group met there and defined concussion as "a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by traumatic biomechanical forces."[7] They agreed that concussion typically involves temporary impairment of neurological function which quickly resolves by itself, and that neuroimaging normally shows no gross structural changes to the brain as the result of the condition.[8]

According to the classic definition, no structural brain damage occurs in concussion;[9] it is a functional state, meaning that symptoms are caused primarily by temporary biochemical changes in neurons, taking place for example at their cell membranes and synapses.[8] However, in recent years researchers have included injuries in which structural damage does occur under the rubric of concussion. According to the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence definition, concussion may involve a physiological or physical disruption in the brain's synapses.[10]

Definitions of mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) have been inconsistent since the 1970s, but the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) described MTBI-related conditions in 1992, providing a consistent, authoritative definition across specialties.[11] In 1993, the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine defined MTBI as 30 minutes or fewer of loss of consciousness (LOC), 24 hours or fewer of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA), and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of at least 13.[12] In 1994, the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders defined MTBI using PTA and LOC.[11] Other definitions of MTBI incorporate focal neurological deficit and altered mental status, in addition to PTA and GCS.[5]

Concussion falls under the classification of mild TBI.[13] It is not clear whether concussion is implied in mild brain injury or mild head injury.[14] "MTBI" and "concussion" are often treated as synonyms in medical literature.[12] However, other injuries such as intracranial hemorrhages (e.g. intra-axial hematoma, epidural hematoma, and subdural hematoma) are not necessarily precluded in MTBI[8] or mild head injury,[15][16] but they are in concussion.[17] MTBI associated with abnormal neuroimaging may be considered "complicated MTBI".[18] "Concussion" can be considered to imply a state in which brain function is temporarily impaired and "MTBI" to imply a pathophysiological state, but in practice few researchers and clinicians distinguish between the terms.[8] Descriptions of the condition, including the severity and the area of the brain affected, are now used more often than "concussion" in clinical neurology.[19]

Although the term "concussion" is still used in sports literature as interchangeable with "MHI" or "MTBI", the general clinical medical literature now uses "MTBI" instead.[20]

Controversy exists about whether the definition of concussion should include only those injuries in which loss of consciousness occurs.[21] Historically, concussion by definition involved a loss of consciousness, but the definition has changed over time to include a change in consciousness, such as amnesia.[22] The best-known concussion grading scales count head injuries in which loss of consciousness does not occur to be mild concussions and those in which it does to be more severe.[23]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of MTBI is based on physical and neurological exams, duration of unconsciousness (usually less than 30 minutes) and post-traumatic amnesia (PTA; usually less than 24 hours), and the Glasgow Coma Scale (MTBI sufferers have scores of 13 to 15).[24] Neuropsychological tests exist to measure cognitive function.[3] The tests may be administered hours, days, or weeks after the injury, or at different times to determine whether there is a trend in the patient's condition.[25] Athletes may be tested before a sports season begins to provide a baseline comparison in the event of an injury.[26]

Health care providers examine head trauma survivors to ensure that the injury is not a more severe medical emergency such as an intracranial hemorrhage. Indications that screening for more serious injury is needed include worsening of symptoms such as headache, persistent vomiting,[27] increasing disorientation or a deteriorating level of consciousness,[28] seizures, and unequal pupil size.[29] Patients with such symptoms, or who are at higher risk for a more serious brain injury, are given MRIs or CT scans to detect brain lesions and are observed by medical staff.

Health care providers make the decision about whether to give a CT scan using the Glasgow Coma Scale.[1] In addition, they may be more likely to perform a CT scan on people who would be difficult to observe after discharge or those who are intoxicated, at risk for bleeding, older than 60,[1] or younger than 16. Most concussions cannot be detected with MRI or CT scans.[30] However, changes have been reported to show up on MRI and SPECT imaging in concussed people with normal CT scans, and post-concussion syndrome may be associated with abnormalities visible on SPECT and PET scans.[18] Mild head injury may or may not produce abnormal EEG readings.[31]

Concussion may be under-diagnosed. The lack of the highly noticeable signs and symptoms that are frequently present in other forms of head injury could lead clinicians to miss the injury, and athletes may cover up their injuries in order to be allowed to remain in the competition.[20] A retrospective survey in 2005 found that more than 88% of concussions go unrecognized.[32]

Diagnosis of concussion can be complicated because it shares symptoms with other conditions. For example, post-concussion symptoms such as cognitive problems may be misattributed to brain injury when they are in fact due to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[33]

Prognosis and lasting effects

MTBI has a mortality rate of almost zero.[24] The symptoms of most concussions resolve within weeks, but problems may persist.[8] It is not common for problems to be permanent, and outcome is usually excellent.[18] People over age 55 may take longer to heal from MTBI or may heal incompletely.[34] Similarly, factors such as a previous head injury or a coexisting medical condition have been found to predict longer-lasting post-concussion symptoms.[35] Other factors that may lengthen recovery time after MTBI include psychological problems such as substance abuse or clinical depression, poor health before the injury or additional injuries sustained during it, and life stress.[18] Longer periods of amnesia or loss of consciousness immediately after the injury may indicate longer recovery times from residual symptoms.[36] For unknown reasons, having had one concussion significantly increases a person's risk of having another.[25] The prognosis may differ between concussed adults and children.[25] Little research has been done on concussion in the pediatric population, but concern exists that severe concussions could interfere with brain development in children.[25]

Post-concussion syndrome

In post-concussion syndrome, symptoms do not resolve for weeks, months, or years after a concussion, and may occasionally be permanent.[37] Symptoms may include headaches, dizziness, fatigue, anxiety, memory and attention problems, sleep problems, and irritability.[38] There is no scientifically established treatment, and rest, a recommended recovery technique, has limited effectiveness.[39] Symptoms usually go away on their own within months.[17] The question of whether the syndrome is due to structural damage or other factors such as psychological ones, or a combination of these, has long been the subject of debate.[33]

Cumulative effects

Cumulative effects of concussions are poorly understood. The severity of concussions and their symptoms may worsen with successive injuries, even if a subsequent injury occurs months or years after an initial one.[40] Symptoms may be more severe and changes in neurophysiology can occur with the third and subsequent concussions.[25] Studies have had conflicting findings on whether athletes have longer recovery times after repeat concussions and whether cumulative effects such as impairment in cognition and memory occur.[41]

Cumulative effects may include psychiatric disorders and loss of long-term memory. For example, the risk of developing clinical depression has been found to be significantly greater for retired football players with a history of three or more concussions than for those with no concussion history.[42] Three or more concussions is also associated with a five-fold greater chance of developing Alzheimer's disease earlier and a three-fold greater chance of developing memory deficits.[42]

Dementia pugilistica

Chronic encephalopathy is an example of the cumulative damage that can occur as the result of multiple concussions or less severe blows to the head. The condition called dementia pugilistica, or "punch drunk" syndrome, which is associated with boxers, can result in cognitive and physical deficits such as parkinsonism, speech and memory problems, slowed mental processing, tremor, and inappropriate behavior.[43] It shares features with Alzheimer's disease.[44]

Second-impact syndrome

Second-impact syndrome, in which the brain swells dangerously after a minor blow, may occur in very rare cases. The condition may develop in people who receive a second blow days or weeks after an initial concussion, before its symptoms have gone away.[45] No one is certain of the cause of this often fatal complication, but it is commonly thought that the swelling occurs because the brain's arterioles lose the ability to regulate their diameter, causing a loss of control over cerebral blood flow.[25] As the brain swells, intracranial pressure rapidly rises.[27] The brain can herniate, and the brain stem can fail within five minutes.[45] Except in boxing, all cases have occurred in athletes under age 20.[46] Due to the very small number of documented cases, the diagnosis is controversial, and doubt exists about its validity.[47]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ropper AH, Gorson KC (2007). "Clinical practice. Concussion". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (2): 166–172. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp064645. PMID 17215534.

- ↑ Shaw NA (2002). "The neurophysiology of concussion". Progress in Neurobiology. 67 (4): 281–344. doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00018-7. PMID 12207973.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1

- ↑ Satz P, Zaucha K, McCleary C, Light R, Asarnow R, Becker D (1997). "Mild head injury in children and adolescents: A review of studies (1970–1995)". Psychological Bulletin. 122 (2): 107–131. PMID 9283296.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1

Comper P, Bisschop SM, Carnide N, Tricco A (2005). "A systematic review of treatments for mild traumatic brain injury". Brain Injury. 19 (11): 863–880. doi:10.1080-0269050400025042 Check

|doi=value (help). ISSN 0269-9052. PMID 16296570. - ↑

- ↑ Cantu RC (2006). "An overview of concussion consensus statements since 2000" (PDF). Neurosurgical Focus. 21 (4:E3): 1–6.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4

- ↑ Parkinson D (1999). "Concussion confusion". Critical Reviews in Neurosurgery. 9 (6): 335–339. doi:10.1007/s003290050153. ISSN 1433-0377.

- ↑ "Head Injury: Triage, Assessment, Investigation and Early Management of Head Injury in Infants, Children and Adults" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. September 2007. ISBN 0-9549760-5-3. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kushner D (1998). "Mild Traumatic brain injury: Toward understanding manifestations and treatment". Archives of Internal Medicine. 158 (15): 1617–1624. PMID 9701095.

- ↑ Lee LK (2007). "Controversies in the sequelae of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury". Pediatric Emergency Care. 23 (8): 580–583. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31813444ea. PMID 17726422.

- ↑ Benton AL, Levin HS, Eisenberg HM (1989). Mild Head Injury. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. v. ISBN 0-19-505301-X.

- ↑ van der Naalt J (2001). "Prediction of outcome in mild to moderate head injury: A review". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 23 (6): 837–851. doi:10.1076/jcen.23.6.837.1018. PMID 11910548.

- ↑ Savitsky EA, Votey SR (2000). "Current controversies in the management of minor pediatric head injuries". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 18 (1): 96–101. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(00)90060-3. PMID 10674544.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Parikh S, Koch M, Narayan RK (2007). "Traumatic brain injury". International Anesthesiology Clinics. 45 (3): 119–135. doi:10.1097/AIA.0b013e318078cfe7. PMID 17622833.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Iverson GL (2005). "Outcome from mild traumatic brain injury". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 301–317. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165601.29047.ae. PMID 16639155.

- ↑ Larner AJ, Barker RJ, Scolding N, Rowe D (2005). The A-Z of Neurological Practice: a Guide to Clinical Neurology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0521629608.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Barth JT, Varney NR, Ruchinskas RA, Francis JP (1999). "Mild head injury: The new frontier in sports medicine". In Varney NR, Roberts RJ. The Evaluation and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. pp. 85–86. ISBN 0-8058-2394-8. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ↑

- ↑ Ruff RM, Grant I (1999). "Postconcussional disorder: Background to DSM-IV and future considerations". In Varney NR, Roberts RJ. The Evaluation and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. p. 320. ISBN 0-8058-2394-8.

- ↑

- ↑ 24.0 24.1

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Moser RS, Iverson GL, Echemendia RJ, Lovell MR, Schatz P, Webbe FM; et al. (2007). "Neuropsychological evaluation in the diagnosis and management of sports-related concussion". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 22 (8): 909–916. PMID 17988831.

- ↑ Maroon JC, Lovell MR, Norwig J, Podell K, Powell JW, Hartl R (2000). "Cerebral concussion in athletes: Evaluation and neuropsychological testing". Neurosurgery. 47 (3): 659–669, discussion 669–672. PMID 10981754.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Cook RS, Schweer L, Shebesta KF, Hartjes K, Falcone RA (2006). "Mild traumatic brain injury in children: Just another bump on the head?". Journal of Trauma Nursing. 13 (2): 58–65. PMID 16884134.

- ↑ Kay A, Teasdale G (2001). "Head injury in the United Kingdom". World Journal of Surgery. 25 (9): 1210–1220. doi:10.1007/s00268-001-0084-6. PMID 11571960.

- ↑ "Facts About Concussion and Brain Injury". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

- ↑

Poirier MP (2003). "Concussions: Assessment, management, and recommendations for return to activity (abstract)". Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 4 (3): 179–185. doi:10.1016/S1522-8401(03)00061-2. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Binder LM (1986). "Persisting symptoms after mild head injury: A review of the postconcussive syndrome". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 8 (4): 323–346. doi:10.1080/01688638608401325. PMID 3091631.

- ↑ Delaney JS, Abuzeyad F, Correa JA, Foxford R (2005). "Recognition and characteristics of concussions in the emergency department population". Journal of Emergency Medicine. 29 (2): 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.01.020. PMID 16029831.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Bryant RA (2008). "Disentangling mild traumatic brain injury and stress reactions". New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (5): 525–527. doi:10.1056/NEJMe078235. PMID 18234757.

- ↑ Alexander MP (1995). "Mild traumatic brain injury: Pathophysiology, natural history, and clinical management". Neurology. 45 (7): 1253–1260. PMID 7617178.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Ryan LM, Warden DL (2003). "Post concussion syndrome". International Review of Psychiatry. 15 (4): 310–316. doi:10.1080/09540260310001606692. PMID 15276952.

- ↑

Boake C, McCauley SR, Levin HS, Pedroza C, Contant CF, Song JX; et al. (2005). "Diagnostic criteria for postconcussional syndrome after mild to moderate traumatic brain injury". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 17 (3): 350–356. doi:doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.17.3.350 Check

|doi=value (help). PMID 16179657. - ↑

- ↑ Harmon KG (1999). "Assessment and management of concussion in sports". American Family Physician. 60 (3): 887–892, 894. PMID 10498114.

- ↑ Pellman EJ, Viano DC (2006). "Concussion in professional football: Summary of the research conducted by the National Football League's Committee on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury" (PDF). Neurosurgical Focus. 21 (4): E12. PMID 17112190.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Cantu RC (2007). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in the National Football League". Neurosurgery. 61 (2): 223–225. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000255514.73967.90. PMID 17762733.

- ↑ Mendez MF (1995). "The neuropsychiatric aspects of boxing". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 25 (3): 249–262. PMID 8567192.

- ↑ Jordan BD (2000). "Chronic traumatic brain injury associated with boxing". Seminars in Neurology. 20 (2): 179–85. doi:10.1055/s-2000-9826. PMID 10946737.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1

- ↑

- ↑ McCrory P (2001). "Does second impact syndrome exist?". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 11 (3): 144–149. PMID 11495318.

Template:Injuries, other than fractures, dislocations, sprains and strains

da:Hjernerystelse

de:Gehirnerschütterung

el:Εγκεφαλική διάσειση

it:Commozione cerebrale

he:זעזוע מוח

nl:Hersenschudding

no:Hjernerystelse

fi:Aivotärähdys

sv:Hjärnskakning