Anthrax pathophysiology

|

Anthrax Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Anthrax pathophysiology On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Anthrax pathophysiology |

|

Risk calculators and risk factors for Anthrax pathophysiology |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

Bacillus anthracis is a rod-shaped Gram-positive bacterium, about 1 by 9 micrometers in size. It was shown to cause disease by Robert Koch in 1877. [2] The bacterium normally rests in endospore form in the soil, and can survive for decades in this state. Once ingested by a ruminant or placed in an open cut, the bacterium begins multiplying inside the animal or human and in a few days to a month kills it. Veterinarians can often tell a possible anthrax induced death by its sudden occurrence and by the blood and bloody fluids that oozed from the body orifices. Most anthrax bacteria inside the body are destroyed by anaerobic bacteria that can grow without oxygen. The greater danger lies in the bodily fluids and blood that spills from the body and spill into the soil where the anthrax bacteria turn into a dormant protective spore form. Once formed the spores are very hard to eradicate.

The infection of ruminants (and occasionally humans) normally proceeds as follows: once the spores are inhaled they are transported through the air passages into the tiny air sacs (alveoli) in the lungs. The spores are then picked up by scavenger cells (macrophages) in the lungs and are transported through small vessels (lymphatics) to the glands (lymph nodes) in the central chest cavity (mediastinum). Damage caused by the anthrax spores and bacilli to the central chest cavity lungs can cause chest pain and difficulty breathing. Once in the lymph glands, the spores germinate into active bacillus, that multiplies, and eventually bursts the macrophage cell, releasing many more bacilli into the bloodstream which are transferred to the entire body. Once in the blood stream these bacilli release a tripartite toxin (composed of lethal factor, edema factor and protective antigen) which is known to be the primary agents of tissue destruction, bleeding, and death. If antibiotics are given too late, even if the antibiotics eradicate the bacteria, some people still will die because the toxins produced by the bacilli still remain in their system at lethal dose levels.

In order to enter the cells, the toxins use another protein produced by B. anthracis, protective antigen. Edema factor inactivates neutrophils (a type of phagocytic cell) so that they cannot phagocytose bacteria. Historically, it was believed that lethal factor caused macrophages to make TNF-alpha and interleukin 1, beta (IL1B), both normal components of the immune system used to induce an inflammatory reaction, ultimately leading to septic shock and death. However, recent evidence indicates that anthrax also targets endothelial cells (cells that lines serous cavities, lymph vessels, and blood vessels), causing vascular leakage (similar to hemorrhagic bleeding), and ultimately hypovolemic shock (low blood volume), and not only septic shock. In other words the patient bleeds to death internally.

The virulence of a strain of anthrax is dependent on multiple factors, primarily the poly-D-glutamic acid capsule that protects the bacterium from phagocytosis by host neutrophils and its toxins, edema toxin and lethal toxin.

Pathophysiology

Exposure

Occupational exposure to infected animals or their products (such as skin wool and meat) is the usual pathway of exposure for humans. Workers who are exposed to dead animals and animal products are at the highest risk, especially in countries where anthrax is more common. Anthrax in livestock grazing on open range where they mix with wild animals still occasionally occurs in the United States and elsewhere. Many workers who deal with wool and animal hides are routinely exposed to low levels of anthrax spores but most exposures are not sufficient to develop anthrax infections. Presumably, the body’s natural defenses can destroy low levels of exposure. These people usually contract cutaneous anthrax if they catch anything. Historically, the most dangerous form of inhalation anthrax was called Woolsorters' disease because it was an occupational hazard for people who sorted wool. Fortunately this is now a very rare form of infection because of the much reduced incidence of anthrax disease in animals. The last fatal case of natural inhalation anthrax in the United States occurred in California in 1976, when a home weaver died after working with infected wool imported from Pakistan. The autopsy was done at UCLA hospital. To minimize the chance of spreading the disease, the deceased was transported to UCLA in a sealed plastic body bag within a sealed metal container. The details of this case have been described in a medical journal Human Pathology (Volume 9, pages 594-597, September, 1978).

In July 2006 an artist who worked with untreated animal skins became the first person in more than 30 years to die in the United Kingdom from anthrax.[1]

Mode of infection

Anthrax can enter the human body through the intestines (ingestion), lungs (inhalation), or skin (cutaneous) and causes distinct clinical symptoms based on its site of entry. An infected human will generally be quarantined. However, anthrax does not usually spread from an infected human to a noninfected human. But if the disease is fatal the person’s body and its mass of anthrax bacilli becomes a potential source of infection to others and special precautions should be used to prevent more contamination. Unfortunately inhalation anthrax, if left untreated until obvious symptoms occur, will usually result in death if treatment is started too late.

Anthrax is usually contracted by handling infected animals or their wool, germ warfare/terrorism or laboratory accidents.

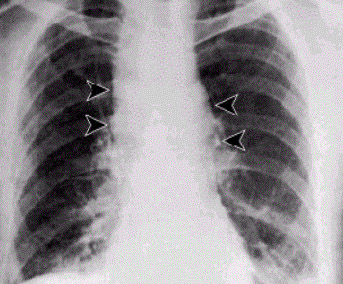

1) Pulmonary (pneumonic, respiratory, or inhalation) anthrax Respiratory infection initially presents with cold or flu-like symptoms for several days, followed by severe (and often fatal) respiratory collapse. If not treated promptly soon after exposure, before symptoms appear, inhalational anthrax is highly fatal, with near 100% mortality.[2] A lethal dose of anthrax is reported to result from inhalation of about 10,000–20,000 spores. [3] Like all diseases there is probably a wide variation to susceptibility with evidence that some people may die from much lower exposures; there is little documented evidence to verify the exact or average number of spores need for infection. Inhalation anthrax is also known as Woolsorters' disease or as Ragpickers' disease since these people often caught it. Other practices associated with exposure include the slicing up of animal horns for the manufacture of buttons, the handling of hair bristles used for the manufacturing of brushes, and the handling of animal skins. Whether these animal skins came from animals that died of the disease or from animals that had simply laid on ground that had spores on it is unknown. Anthrax is a very hard disease to eliminate since Anthrax spores are devilishly hard to kill and have been known to have reinfected animals over 70 years after burial sites of anthrax infected animals were disturbed. [4]

2) Gastrointestinal (gastroenteric) anthrax Gastrointestinal infection is most often caused by eating anthrax infected meat and is characterized by serious gastrointestinal difficulty, vomiting of blood, severe diarrhea, acute inflammation of the intestinal tract, and loss of appetite. Gastrointestinal infections can be treated but usually result in fatality rates of 25% to 60%, depending upon how soon treatment commences. [5]

3) Cutaneous (skin) anthrax

Cutaneous (on the skin) anthrax infection shows up as a boil-like skin lesion that eventually forms an ulcer with a black center (i.e., eschar). The black eschar often shows up as a large, painless necrotic ulcers (beginning as an irritating and itchy skin lesion or blister that is dark and usually concentrated as a black dot, somewhat resembling bread mold) at the site of infection. Cutaneous infections generally form within the site of spore penetration within 2 to 5 days after exposure. Unlike bruises or most other lesions, cutaneous anthrax infections normally do not cause pain. Cutaneous infection is the least fatal form of anthrax infection if treated. But without treatment, approximately 20% of all cutaneous skin infection cases may progress to toxemia and death. [6] Treated cutaneous anthrax is rarely fatal.[2]

References

- ↑ Artist dies from anthrax caught from animal skins Independent News and Media Limited, 17 August 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bravata DM, Holty JE, Liu H, McDonald KM, Olshen RA, Owens DK (2006), Systematic review: a century of inhalation anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005, Annals of Internal Medicine; 144(4): 270–80.

- ↑ "www.medicinenet.com". Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ↑ "Anthrax" by Jeanne Guillemin, University of California Press, 2001,ISBN 0-520-22917-7, pg. 3

- ↑ "Anthrax Q & A: Signs and Symptoms". Emergency Preparedness and Response. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ "Anthrax Q & A: Signs and Symptoms". Emergency Preparedness and Response. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2003. Retrieved 2007-04-19.