Abreugraphy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{Tuberculosis}} | ||

{{CMG}} | {{CMG}} | ||

Revision as of 18:22, 22 February 2012

|

Tuberculosis Microchapters |

|

Diagnosis |

|---|

|

Treatment |

|

Case Studies |

|

Abreugraphy On the Web |

|

American Roentgen Ray Society Images of Abreugraphy |

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]

Overview

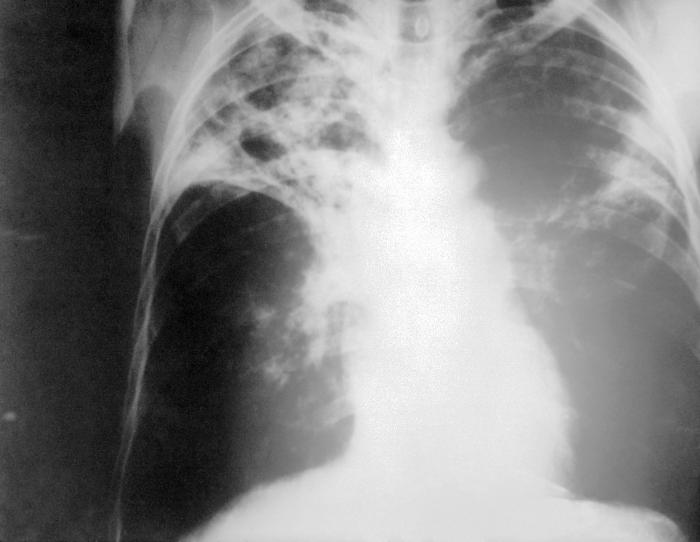

Abreugraphy is a technique for mass screening of tuberculosis using a miniature (50 to 100 mm) photograph of the screen of a x-ray fluoroscopy of the thorax, first developed in 1935.

Historical Perspective

Abreugraphy receives its name from its inventor, Dr. Manuel Dias de Abreu, a Brazilian physician and pulmonologist. It has received several different names, according to the country where it was adopted: mass radiography, miniature chest radiograph (United Kingdom and USA), roentgenfluorography (Germany), radiophotography (France), schermografia (Italy), photoradioscopy (Spain) and photofluorography (Sweden).

In many countries, miniature mass radiographs (MMR) was quickly adopted and extensively utilized in the 1950s. For example, in Brazil and in Japan, tuberculosis prevention laws went into effect, obligating ca. 60% of the population to undergo MMR screening. However, as a mass screening program for low-risk populations, the procedure was largely discontinued in the 1970s, following recommendation of the World Health Organization, due to three main reasons:

- The dramatic decrease of the general incidence of tuberculosis in developed countries (from 150 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 1900, 70/100,000 in 1940 and 5/100,000 in 1950);

- Decreased benefits/cost ratio (a recent Canadian study [2] has shown a cost of CD$ 236,496 per case in groups of immigrants with a low risk for tuberculosis, versus CD$ 3,943 per case in high risk groups);

- Risk of exposure to ionizing radiation doses, particularly among children, in the presence of extremely low yield rates of detection.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

MMR is still an easy and useful way to prevent transmission of the disease in certain situations, such as in prisons and for immigration applicants and foreign workers coming from countries with a higher risk for tuberculosis. Currently, 13 of the 26 European countries use MMR as the primary screening tool for this purpose. Examples of countries with permanent programs are Italy, Switzerland, Norway, Netherlands, Japan and the United Kingdom. [1]

For example, a study in Switzerland [3] between 1988 and 1990, employing abreugraphy to detect tuberculosis in 50,784 immigrants entering the canton of Vaud, discovered 674 foreign people with abnormalities. Of these, 256 had tuberculosis as the primary diagnosis and 34 were smear or culture-positive (5% of all radiological abnormalities). [2]

Elderly populations are also a good target for MMR-based screening, because the radiation risk is less important and because they have a higher risk of tuberculosis (85 per 100,000 in developed countries, in the average). In Japan, for example, it is still used routinely, and the Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association (JATA) reported the detection of 228 cases in 965,440 chest radiographs in 1996 alone [4].[3]

MMR is most useful at detecting tuberculosis infection in the asymptomatic phase, and it should be combined with tuberculin skin tests and clinical questioning in order to be more effective. The sharp increase in tuberculosis in all countries with large exposure to HIV is probably mandating a return of MMR as a screening tool focusing on high-risk populations, such as homosexuals and intravenous drug users. New advances in digital radiography, coupled with much lower x-ray dosages may herald better MMR technologies.

References

- ↑ Schwartzman K, Menzies D. Tuberculosis screening of immigrants to low-prevalence countries. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Mar;161(3 Pt 1):780-9. PMID 1071232

- ↑ Bonvin L, Zellweger JP. Mass miniature X-ray screening for tuberculosis among immigrants entering Switzerland. Tuber Lung Dis. 1992 Dec;73(6):322-5. PMID 1292710

- ↑ Ohmori M, Wada M, Uchimura K, Nishii K, Shirai Y, Aoki M. Discussing the current situation of tuberculosis case-finding by mass miniature radiography in Japan. Kekkaku. 2002 Apr;77(4):329-39. In Japanese. PMID 12030038