Sandbox: Reddy

Candida Vulvovaginitis

Historical Perspective

- In 1839, B. Lagenbeck from Germany described a yeast-like fungus for the first time in the human oral infection "thrush." and its ability to cause it.[1]

- In 1923 the Candida albicans was described by Christine Marie Berkhout. Over the years the classification of the genera and species has evolved. Obsolete names for this genus include Mycotorula and Torulopsis. The species has also been known in the past as Monilia albicans and Oidium albicans. The current classification is nomen conservandum, which means the name is authorized for use by the International Botanical Congress (IBC).

- The full current taxonomic classification is available at Candida albicans.

- The genus Candida includes about 150 different species. However, only a few of those are known to cause human infections. C. albicans is the most significant pathogenic (=disease-causing) species. Other Candida species causing diseases in humans include C. tropicalis, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, C. dubliniensis, and C. lusitaniae.

Classification

Candida vulvovaginitis can be classified based on the duration, as well as the strain of Candida causing the infection.

Duration

Candida vulvovaginitis can be divided based on the duration and number of episodes of the infection into:[2][3][4][5]

- Acute, uncomplicated: these are usually sporadic cases of Candida vulvovaginitis, which respond to topical anti-fungal therapy and have a high cure rate.

- Acute, complicated: symptoms are more severe than uncomplicated infections and typically require a combination of oral and topical anti-fungal treatment.

- Recurrent: defined as 4 or more episodes of Candida vulvovaginitis per year, usually caused by the same strain of Candida. Treatment also requires a combination of oral and topical anti-fungal agents.

Microbiology

Candida vulvovaginitis can also be divided based on the strain of Candida causing the infection:[4][6]

- C. albicans: comprises the majority of cases of Candida vulvovaginitis

- C. glabrata: it is the second most common causative pathogen

- C. tropicalis

- C. krusei

- C. parapsilosis

Pathophysiology

Vaginal Defensive mechanisms aganist Candida

Innate Mechanisms

| Defense | Mechanism of protection | Evidence of protection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vaginal epithelial cells |

|

|

| 2 | Mannose-binding lectin |

|

|

| 3 | Activated lactoferrin |

|

|

| 4 | Vaginal bacterial flora |

|

|

| 5 | Phagocytic systems/polymononuclear leucocytes, mononuclear cells, complement |

|

|

Adaptive Mechanisms

| Defense | Mechanism | Role in Protection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immunoglobulin mediated immunity | Systemic IgM, IgG and local IgA antibodies are produced in response to the infection |

|

| 2 | Cell Mediated Immunity |

Interleukin 4 (Th2) inhibits anti-candida activity of nitric oxide and protective pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines. |

|

Candida Virulence Factors

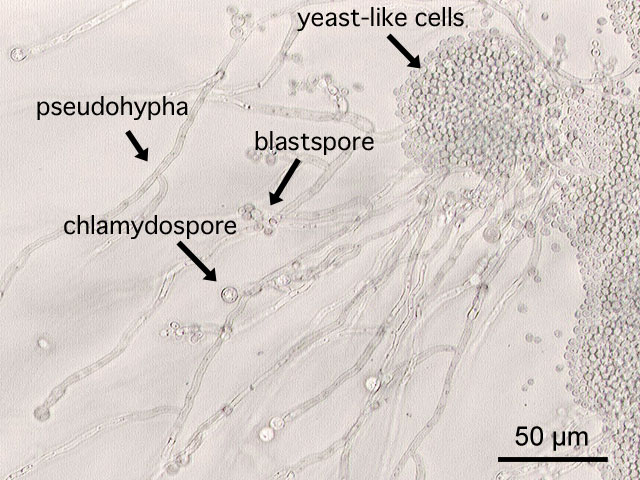

- C.albicans in forms vitro blastospores, germ tubes, pseudomycelia, rue mycelia and also chlamydospores on special culture media. C. glabrata exists exclusively in blastospores.

- All strains of Candida species possess a yeast surface mannoprotein which helps in adhering to epithelial cells of the vagina.[4][7]

- Germination of the spores helps in colonizing the vagina.

- Proteolytic enzymes, toxins and phospholipase destroy the proteins that normally impair fungal invasion, enhancing the ability of Candida to colonize the vagina.[4][7][8]

- Phenotypic switching of Candida is described in patients with recurrent vaginitis.

- C.albicans can form bio-films on the intra uterine devices or sponges causing disease recurrence.

Pathogenesis

- Candida vulvovaginitis is a microbial disease and not all patients with detectable pathogen are symptomatic. Multiple risk factors and the imbalance in the protective vaginal defenses predispose patients to develop active disease.

- Candida vaginal infections are more common in the reproductive age group because of the high concentration of estrogen. It increases the amount of glycogen in the vagina providing a carbon source for candida organisms to colonize and also increases the adherence of candida to the vaginal epithelial cells.

- The most common source of the infection is from the peri-anal area. Other less common source is sexual transmission and persistance of organisms in the vagina after treatment, responsible for recurrence.

- The course of the infection begins with colonization, symptoms appear with the invasion of the blastospores or pseudohyphae of the vaginal wall.

- The understanding of the transition from asymptomatic vaginal colonization with Candida to symptomatic vulvovaginitis is not clear.[7][8]

Genetics

- Few genetic factors are thought to be involved in patients with recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis.

- Supporting evidence is that many cases were found to be more common in African-American women, run in families, as well as being associated with ABO-Lewis non-secretor phenotype, a rare blood group.

- In addition, women with Candida vulvovaginitis were found to have decreased concentrations of mannose binding lectin (MBL), hence, the variant (MBL) gene is thought to be a contributing factor in the development of Candida vulvovaginitis.[4][9][10]

Gross Pathology

On speculum examination typical curdy white discharge is present.

-

This photograph is a speculum examination of the vagina with Candida infection and the typical thick, curdy vaginal discharge.

Microscopic Pathology

-

This is a a microscopic image of Candida albicans, grown on cornmeal agar medium.

-

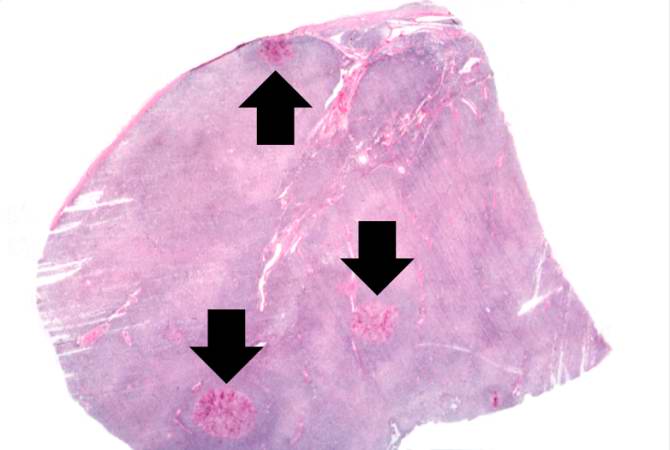

This is a low-power photomicrograph of lymph node with three prominent areas of Candida colonies (arrows). Even at this low magnification, the purple-staining yeast and pseudohyphae can be easily seen. This section was stained with Periodic Acid-Schiff Hematoxylin (PASH), which stains the cell wall of fungi to make them more easily visible.

-

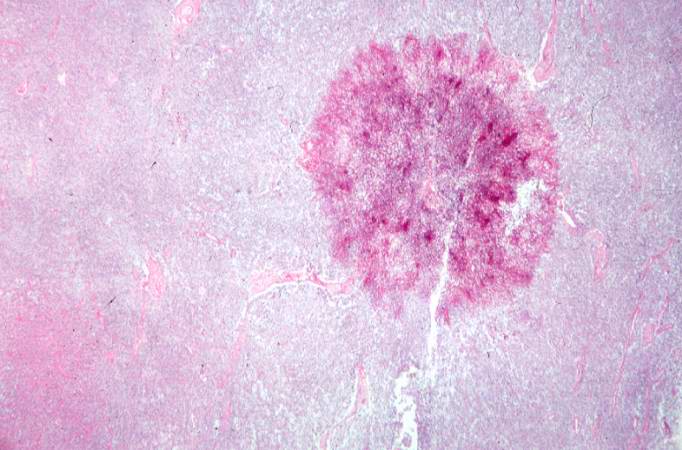

This is a low-power photomicrograph of one of the Candida colonies from this lymph node. The chains of yeast which are termed "pseudohyphae" are apparent at this magnification.

-

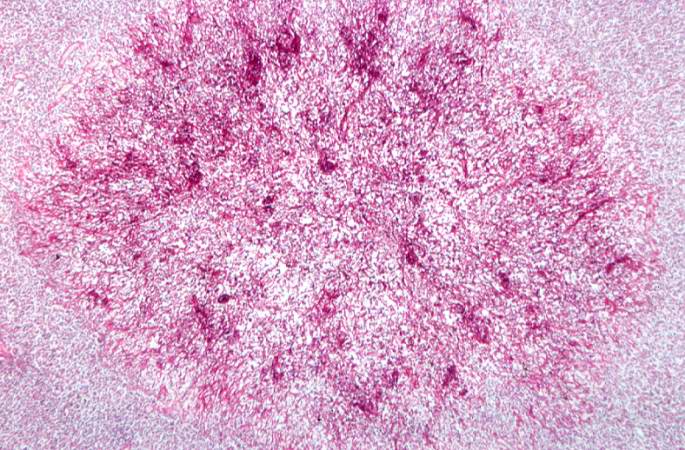

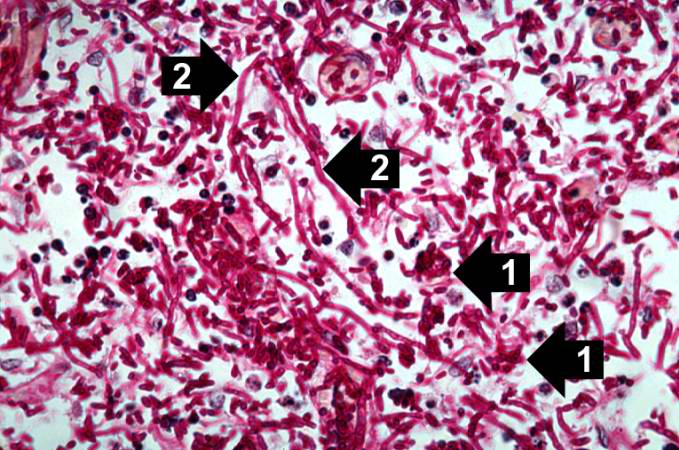

This higher-power photomicrograph shows the yeasts and pseudohyphae in this focus of Candida organisms.

-

This high-power photomicrograph shows the yeasts (1) and pseudohyphae (2).

Associated Conditions

- Candida vulvovaginitis may be associated with other pathogens that cause vulvovaginitis which include Trichomonas vaginalis and Gardnerella vaginalis. The presence of these diseases in combination is common therefore they must be excluded before initiation of treatment.[11][12]

Causes

Candida vulvovaginitis is caused by many different species of Candida. They are divided into Candida albicans and Candida non-albicans species based on the causative pathogen:

Common Causes

- Candida albicans: These strains are isolated in 85 to 95% patients with yeast infection.[13]

- Candida non albicans: Candida glabrata is the most common isolated pathogen in this group affecting 10 to 20% of women and is associated with recurrent Candida vulvovaginitis.[14]

Less Common Causes

These are less commonly isolated in patients but is important to identify the species as they are less sensitive to standard azole therapy causing recurrent infection.[15][16]

Differentiating Candida Vulvovaginitis from other Diseases

Candida Vulvovaginitis must be differentiated from the following diseases which have a similar presentation:[19][20][21][22][23]

| Disease | Findings |

|---|---|

| Trichomoniasis |

|

| Atrophic vaginitis |

|

| Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis |

|

| Bacterial Vaginosis |

|

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Epidemiological studies on Candida vulvovaginitis are hard to perform, because of several factors:[3][4]

- Candida vulvovaginitis is not a reportable disease.

- The diagnosis of Candida vulvovaginitis is based on clinical presentation and positive laboratory findings. Relying on a positive culture alone would likely overestimate the prevalence of Candida vulvovaginitis.

- The use of over-the-counter (OTC) topical anti-fungals makes it difficult to conduct epidemiological studies.

- Candida is the second most common cause of vaginal infection in young women following Bacterial Vaginosis.[24]

Age

- Incidence of Candida vulvovaginitis is higher in pregnant women.[25][26]

- Women in reproductive age group are prone for Candida vulvovaginits and at least one episode is reported in 70 to 75% in this population group.[27]

- 40 to 50% of patients with a prior yeast infection have multiple episodes of yeast infection.[25]

- Among the adult population 5 to 8% women have more than four episodes of infection.[28]

- In 20% asymptomatic healthy adolescent women, candida species is isolated from the vagina.[29]

Race

Candida vulvovaginitis is more prevalent among African American women than white American women.[28]

Risk Factors

The following risk factors have been implicated in predisposing patients to Candida vulvovaginitis:

- Previous infection with Candida vulvovaginitis[30]

- Previous infection with Neisseria gonorrhea[31]

- Nulliparity[2]

- Luteal phase of the menstrual cycle [2]

- Recent antibiotic use[32]

- Pregnancy[2]

- Diabetes Mellitus[33][34]

- Obesity

- Immunosuppression, such as HIV or glucocorticoid use[35]

- Condom use[36]

Risk Factors for Recurrent Candida Vulvovaginitis

| Microbial Factors | Genetic Factors | Host Behavioural Factors | Other Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Table adopted from Vulvovaginal candidiasis Lancet 2007; 369: 1961–71[4]

Natural History, Complications and Prognosis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Candida vulvovaginitis requires a correlation of clinical features, microscopic examination, and vaginal culture.

History and Symptoms

Symptoms of vulvovaginitis caused by Candida species are indistinguishable and include the following:[37][2][3]

- Pruritus is the most significant symptom

- Change in the amount and the color of vaginal discharge: It is characterized by a thick, white "cottage cheese-like" vaginal discharge

- Pain on urination (dysuria)

- Pain on sexual intercourse (dyspareunia)

- Vulvovaginal soreness

- Symptoms aggravate a week before the menses

Physical Examination

Candida vulvovaginitis requires a careful examination of the external genitalia, the vaginal sidewalls, as well as the cervix. Signs include:[38][2]

- Edema and erythema of the vulva and labia

- Fissures and excoriations of the external genitalia

- Thick adherent whitish vaginal discharge

- Cervix is not affected and is normal

Laboratory Findings

The laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of Candida vulvovaginitis include:[2][39][4]

- Vaginal pH: In Candida vulvovaginitis the vaginal pH is normal (ranges from 4.0-4.5)

- Wet mount or Saline preparation: It will help in detection of hyphae, clue cells and motile trichomonas differentiating different causes of vaginitis.

- 10% Potassium hydroxide preparation: It is more sensitive than wet mount to show budding blastospores or pseudohyphae.

- Culture: Culture for diagnosing Candida vulvovaginitis not recommended in patients with positive microscopy. However, it should be done in a symptomatic woman with a negative microscopy and a normal vaginal pH. Culture using Sabouraud agar, Nickerson’s medium, or Microstix-candida medium identify Candida species with equal sensitivity.

Treatment

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy for Candida vulvovaginitis includes:

- Uncomplicated candida Vulvovaginits:

- 1st line :Any topical antifungal agents can be used and all of them have equal efficacy

- Alternative : Single 150mg dose of oral fluconazole is recommended.

- Severe acute Candida vulvovaginitis:

- 1st line: Oral fluconazole 150mg, given every 72 hours for a total of 2 or 3doses

- Candida glabrata: When unresponsive to oral azoles

- 1st line: Topical intravaginal boric acid administered in a gelatin capsule, 600mg daily for 14days

- 2nd line: Nystatin intravaginal suppositories, 100,000 units daily for 14days

- 3rd line: Topical 17% flucytosine cream alone or in combination with amphotericin B cream daily for 14days

- Recurring vulvovaginal candidiasis:

- 1st line: 10 to 14days of induction therapy with a topical agent or oral fluconazole, followed by fluconazole, 150mg weekly for 6months

Candida Vulvovaginitis in HIV positive women

Surgical Therapy

Prevention

- Prophylactic maintainence of fluconazole is helpful in patients with idiopathic recurrent candida vulvovaginitis and in secondary recurrent vulvovaginitis associated with lichen sclerosus or topical estrogen application.

References

- ↑ Barnett JA (2008). "A history of research on yeasts 12: medical yeasts part 1, Candida albicans". Yeast. 25 (6): 385–417. doi:10.1002/yea.1595. PMID 18509848.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Eckert LO (2006). "Clinical practice. Acute vulvovaginitis". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (12): 1244–52. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp053720. PMID 16990387.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sobel JD, Faro S, Force RW, Foxman B, Ledger WJ, Nyirjesy PR, Reed BD, Summers PR (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiologic, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 178 (2): 203–11. PMID 9500475.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Sobel JD (2007). "Vulvovaginal candidosis". Lancet. 369 (9577): 1961–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. PMID 17560449.

- ↑ Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, Demitriou R, Vaishampayan J, Lynch M, Zervos MJ (1994). "Karyotyping of Candida albicans isolates obtained longitudinally in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". J. Infect. Dis. 170 (6): 1566–9. PMID 7995997.

- ↑ Buscemi L, Arechavala A, Negroni R (2004). "[Study of acute vulvovaginitis in sexually active adult women, with special reference to candidosis, in patients of the Francisco J. Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital]". Rev Iberoam Micol. 21 (4): 177–81. PMID 15709796.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sobel JD (1985). "Epidemiology and pathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 152 (7 Pt 2): 924–35. PMID 3895958.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sobel JD (1989). "Pathogenesis of Candida vulvovaginitis". Curr Top Med Mycol. 3: 86–108. PMID 2688924.

- ↑ Liu F, Liao Q, Liu Z (2006). "Mannose-binding lectin and vulvovaginal candidiasis". Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 92 (1): 43–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.08.024. PMID 16256117.

- ↑ Donders GG, Babula O, Bellen G, Linhares IM, Witkin SS (2008). "Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism and resistance to therapy in women with recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis". BJOG. 115 (10): 1225–31. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01830.x. PMID 18715406.

- ↑ Sobel JD, Subramanian C, Foxman B, Fairfax M, Gygax SE (2013). "Mixed vaginitis-more than coinfection and with therapeutic implications". Curr Infect Dis Rep. 15 (2): 104–8. doi:10.1007/s11908-013-0325-5. PMID 23354954.

- ↑ Anderson MR, Klink K, Cohrssen A (2004). "Evaluation of vaginal complaints". JAMA. 291 (11): 1368–79. doi:10.1001/jama.291.11.1368. PMID 15026404.

- ↑ Corsello S, Spinillo A, Osnengo G, Penna C, Guaschino S, Beltrame A; et al. (2003). "An epidemiological survey of vulvovaginal candidiasis in Italy". Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 110 (1): 66–72. PMID 12932875.

- ↑ Okungbowa FI, Isikhuemhen OS, Dede AP (2003). "The distribution frequency of Candida species in the genitourinary tract among symptomatic individuals in Nigerian cities". Rev Iberoam Micol. 20 (2): 60–3. PMID 15456373.

- ↑ Bauters TG, Dhont MA, Temmerman MI, Nelis HJ (2002). "Prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis and susceptibility to fluconazole in women". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 187 (3): 569–74. PMID 12237629.

- ↑ Holland J, Young ML, Lee O, C-A Chen S (2003). "Vulvovaginal carriage of yeasts other than Candida albicans". Sex Transm Infect. 79 (3): 249–50. PMC 1744683. PMID 12794215.

- ↑ Nyirjesy P, Alexander AB, Weitz MV (2005). "Vaginal Candida parapsilosis: pathogen or bystander?". Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 13 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1080/10647440400025603. PMC 1784559. PMID 16040326.

- ↑ Singh S, Sobel JD, Bhargava P, Boikov D, Vazquez JA (2002). "Vaginitis due to Candida krusei: epidemiology, clinical aspects, and therapy". Clin Infect Dis. 35 (9): 1066–70. doi:10.1086/343826. PMID 12384840.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Bacterial Vaginosis. http://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/bv.htm Accessed on October 13, 2016

- ↑ Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS (2000). "Diagnosis and treatment of atrophic vaginitis". Am Fam Physician. 61 (10): 3090–6. PMID 10839558.

- ↑ Krieger JN, Tam MR, Stevens CE, Nielsen IO, Hale J, Kiviat NB; et al. (1988). "Diagnosis of trichomoniasis. Comparison of conventional wet-mount examination with cytologic studies, cultures, and monoclonal antibody staining of direct specimens". JAMA. 259 (8): 1223–7. PMID 2448502.

- ↑ Sobel JD, Reichman O, Misra D, Yoo W (2011). "Prognosis and treatment of desquamative inflammatory vaginitis". Obstet Gynecol. 117 (4): 850–5. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182117c9e. PMID 21422855.

- ↑ Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (5): 757–65. PMID 9794664.

- ↑ Allsworth JE, Peipert JF (2007). "Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data". Obstet Gynecol. 109 (1): 114–20. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000247627.84791.91. PMID 17197596.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hurley R, De Louvois J (1979). "Candida vaginitis". Postgrad Med J. 55 (647): 645–7. PMC 2425644. PMID 523355.

- ↑ García Heredia M, García SD, Copolillo EF, Cora Eliseth M, Barata AD, Vay CA; et al. (2006). "[Prevalence of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women. Identification of yeasts and susceptibility to antifungal agents]". Rev Argent Microbiol. 38 (1): 9–12. PMID 16784126.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Andrea; Romano, Mary (2016). "Clinical Recommendation: Vulvovaginitis". Journal of Pediatric and AdolescentGynecology. 29 (6): 673–679. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.08.002. ISSN 1083-3188.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Foxman B, Marsh JV, Gillespie B, Sobel JD (1998). "Frequency and response to vaginal symptoms among white and African American women: results of a random digit dialing survey". J Womens Health. 7 (9): 1167–74. PMID 9861594.

- ↑ Barousse, M M (2004). "Vaginal yeast colonisation, prevalence of vaginitis, and associated local immunity in adolescents". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 80 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1136/sti.2002.003855. ISSN 1368-4973.

- ↑ Foxman B (1990). "The epidemiology of vulvovaginal candidiasis: risk factors". Am J Public Health. 80 (3): 329–31. PMC 1404680. PMID 2305918.

- ↑ Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (5): 757–65. PMID 9794664.

- ↑ Wilton L, Kollarova M, Heeley E, Shakir S (2003). "Relative risk of vaginal candidiasis after use of antibiotics compared with antidepressants in women: postmarketing surveillance data in England". Drug Saf. 26 (8): 589–97. PMID 12825971.

- ↑ de Leon EM, Jacober SJ, Sobel JD, Foxman B (2002). "Prevalence and risk factors for vaginal Candida colonization in women with type 1 and type 2 diabetes". BMC Infect. Dis. 2: 1. PMC 65518. PMID 11835694.

- ↑ Donders GG (2002). "Lower Genital Tract Infections in Diabetic Women". Curr Infect Dis Rep. 4 (6): 536–539. PMID 12433331.

- ↑ Duerr A, Heilig CM, Meikle SF, Cu-Uvin S, Klein RS, Rompalo A, Sobel JD (2003). "Incident and persistent vulvovaginal candidiasis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women: Risk factors and severity". Obstet Gynecol. 101 (3): 548–56. PMID 12636961.

- ↑ Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (5): 757–65. PMID 9794664.

- ↑ Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (5): 757–65. PMID 9794664.

- ↑ Eckert LO, Hawes SE, Stevens CE, Koutsky LA, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK (1998). "Vulvovaginal candidiasis: clinical manifestations, risk factors, management algorithm". Obstet Gynecol. 92 (5): 757–65. PMID 9794664.

- ↑ Mendling W, Brasch J (2012). "Guideline vulvovaginal candidosis (2010) of the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics, the Working Group for Infections and Infectimmunology in Gynecology and Obstetrics, the German Society of Dermatology, the Board of German Dermatologists and the German Speaking Mycological Society". Mycoses. 55 Suppl 3: 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02185.x. PMID 22519657.