Psychodynamics

Please Take Over This Page and Apply to be Editor-In-Chief for this topic: There can be one or more than one Editor-In-Chief. You may also apply to be an Associate Editor-In-Chief of one of the subtopics below. Please mail us [1] to indicate your interest in serving either as an Editor-In-Chief of the entire topic or as an Associate Editor-In-Chief for a subtopic. Please be sure to attach your CV and or biographical sketch.

Overview

Psychodynamics is a psychological analogy of the transient function(s) of the mind, drawn from (amongst other things) the practice of neurology, and the principles of thermodynamics. In more detail, psychodynamics is the study of human behavior from the point of view of motivation and drives, depending largely on the functional significance of emotion, and based on the assumption that an individual's total personality and reactions at any given time are the product of the interaction between their conscious/unconscious mind, genetic constitution and their environment.[1] In medical practice, psychodynamics is defined as the systematized study and theory of the psychological forces that underlie human behavior, emphasizing the interplay between unconscious and conscious motivation and the functional significance of emotion.[2] The original concept of "psychodynamics" was developed by Sigmund Freud who, in the late 1870s, began to apply the principles of thermodynamics, predominantly those of Hermann von Helmholtz, to psychology.[3] Freud suggested that psychological processes are flows of psychological energy in a complex brain, establishing "psychodynamics" on the basis of psychological energy, which he referred to as libido.

Overview

In general, psychodynamics, also known as dynamic psychology, is the study of the interrelationship of various parts of the mind, personality, or psyche as they relate to mental, emotional, or motivational forces especially at the unconscious level.[4][5][6] The mental forces involved in psychodynamics are often divided into two parts:[7] (a) interaction of emotional forces: the interaction of the emotional and motivational forces that affect behavior and mental states, especially on a subconscious level; (b) inner forces affecting behavior: the study of the emotional and motivational forces that affect behavior and states of mind;.

Based on the principles of thermodynamics of closed systems, Freud proposed that psychological energy was constant (hence, emotional changes consisted only in displacements) and that it tended to rest (point attractor) through discharge (catharsis).[8]

In mate selection psychology, psychodynamics is defined as the study of the forces, motives, and energy generated by the deepest of human needs.[9]

In general, psychodynamics studies the transformations and exchanges of "psychic energy" within the personality.[5] A focus in psychodynamics is the connection between the energetics of emotional states in the id, ego, and superego as they relate to early childhood developments and processes. At the heart of psychological processes, according to Freud, is the ego, which he envisions as battling with three forces: the id, the super-ego, and the outside world.[4] Hence, the basic psychodynamic model focuses on the dynamic interactions between the id, ego, and superego.[10] Psychodynamics, subsequently, attempts to explain or interpret behavior or mental states in terms of innate emotional forces or processes.

History

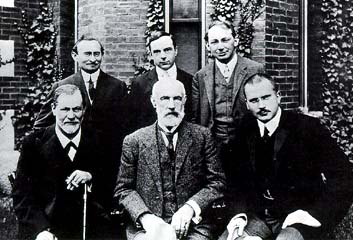

The concept of psychodynamics was seeded with the 1874 publication of Lectures on Physiology by German physiologist Ernst von Brücke who, in coordination with physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, one of the founders of the first law of thermodynamics (conservation of energy), proffered that all living organisms are energy-systems also governed by this principle.[6][5] During this year, at the University of Vienna, Brucke was also coincidentally the supervisor for first-year medical student Sigmund Freud who naturally adopted this new “dynamic” physiology. Later, the theory of psychodynamics was developed further by such people as Carl Jung, Alfred Adler and Melanie Klein.

By the mid 1940s and into the 1950s, the general application of the "psychodynamic theory" had been well established. In his 1988 book Introduction to Psychodynamics - a New Synthesis, psychologist Mardi J. Horowitz states that his own interest and fascination with psychodynamics began during the 1950s, when he heard Ralph Greenson, a popular local psychoanalyst who spoke to the public on topics such as “People who Hate”, speak on the radio at UCLA. In his radio discussion, according to Horowitz, he “vividly described neurotic behavior and unconscious mental processes and linked psychodynamics theory directly to everyday life.”[11]

In the 1950s, American psychiatrist Eric Berne built on Freud's psychodynamic model, particularly that of the "ego states", to develop a psychology of human interactions called transactional analysis.[12] Transactional analysis, according to physician James R. Allen, is a "cognitive behavioral approach to treatment and that it is a very effective way of dealing with internal models of self and others as well as other psychodynamic issues."[12] The theory was popularized in the 1964 book Games People Play, a book that sold five-million copies, giving way to such catch prases as “Boy, has he got your number” and others.

Freudian psychodynamics

The central premise of psychodynamics, originating through the work of Freud, is based on the first law of thermodynamics, which states that the total amount of matter and energy in any system under study, which undergoes any transformation or process, is conserved. Translating this physical law into a psychological concept, Freud hypothesized that experiences, especially early childhood experiences, in theory, are conserved in the unconscious. Subsequently, conserved experiences later in life must either remain buried in the mind or find their way to the surface, i.e. the “conscious” level. This, in the former case, results in psychological states such as neurosis and psychosis. In sum, according to American psychologist Calvin S. Hall, from his 1954 Primer in Freudian Psychology:

| “ | Freud greatly admired Brücke and quickly became indoctrinated by this new dynamic physiology. Thanks to Freud’s singular genius, he was to discover some twenty years later that the laws of dynamics could be applied to man’s personality as well as to his body. When he made his discovery Freud proceeded to create a dynamic psychology. A dynamic psychology is one that studies the transformations and exchanges of energy within the personality. This was Freud’s greatest achievement, and one of the greatest achievements in modern science, It is certainly a crucial event in the history of psychology. | ” |

At the heart of psychological processes, according to Freud, is the ego, which he sees battling with three forces: the id, the super-ego, and the outside world.[4] Hence, the basic psychodynamic model focuses on the dynamic interactions between the id, ego, and superego.[10] Psychodynamics, subsequently, attempts to explain or interpret behavior or mental states in terms of innate emotional forces or processes. In his writings about the "engines of human behavior", Freud used the German word Trieb, a word that can be translated into English as either instinct or drive.[13]

In the 1930s, Freud's daughter Anna Freud began to apply Freud's psychodynamic theories of the "ego" to the study of parent-child attachment and especially deprivation and in doing so developed ego psychology.

Jungian psychodynamics

At the turn of the 20th century, during these decisive years, a young Swiss psychiatrist named Carl Jung had been following Freud’s writings and had sent him copies of his articles and his first book, the 1907 Psychology of Dementia Praecox, in which he upheld the Freudian psychodynamic viewpoint, although with some reservations. That year, Freud invited Jung to visit him in Vienna. The two men, it is said, were greatly attracted to each other, and they talked continuously for thirteen hours. This led to a professional relationship in which the corresponded on a weekly basis, for a period of six years.[14]

Building on the work of Freud, Jung advanced the framework of psychodynamics. According to Jung, the mental sphere, having conscious and unconscious parts, is divided up into a number of interacting relatively closed systems. The total set of such mental systems takes in energy via sensor input, which energizes the person; however, the dynamic distribution of these inputs among the various systems is governed by two principles.[14]

- Principle of Equivalence – if the amount of energy consigned to a given psychic element decreases or disappears, that amount of energy will appear in another psychic element.

- Principle of Entropy – the distribution of energy in the psyche seeks equilibrium or balance among all the structures of the psyche.

Jung modeled these psychological energetic principles on the first law of thermodynamics and the second law of thermodynamics, respectively. The key concepts in Jungian psychodynamics are psychic energy or libido, value, equivalence, entropy, progression and regression, and canalization.[15]

Positive psychology

In positive psychology, the psychodynamic conception of flow is defined as a conscious state of mind in harmonious order. In simple terms, it is a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great costs, for the sake of doing it.[16] In other words, in positive psychology, flow is a state of mental activity or operation in which the person is fully immersed in what he or she is doing, characterized by energized focus, full involvement, and success in the process of the activity.

The concept of flow in relation to mental contentment was developed by American psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi who, beginning in the 1970s, interviewed and studied hundreds of successful people, such as musicians, athletes, artists, chess masters, and surgeons. In his studies, he made people wear “flow timers” in which at various randomized times during their workday a timer would go off and they document their flow state on paper. He then combined these data sets with Freud’s dynamics views on social forces and psychological forces, psychic energy, psychic entropy, and his thoughts on consciousness and intentions, to derive what he calls “flow theory”. Among his many books on this subject, the pinnacle publication was the 1990 book Flow – the Psychology of Optimal Experience, which introduced the world to the psychological concept of flow and optimal experience.[17]

In this book, he states that “our perceptions about our lives are the outcome of many forces that shape our experience, each having an impact on whether we fell good or bad.” In addition, what we call intentions, he says, ‘is the force that keeps information in consciousness ordered. Intentions arise in the consciousness whenever a person is aware of desiring something or wanting to accomplish something.” He states, by analogy, that intentions “act as magnetic fields, moving attention toward some objects and away from others, keeping our mind focused on some stimuli in preference to others.” To exemplify, he says, for instance, the “hunger drive that organized the content of the consciousness, forces us to focus attention on food.” Csíkszentmihályi argues that similar forces cause us to focus attention on more dominant tasks, such as a person’s life work, passionate hobby, or adventure, etc.

Current

Presently, psychodynamics is an evolving multi-disciplinary field which analyzes and studies human thought process, response patterns, and influences. Research in this field provides insights into a number of areas, including:[18]

- Understanding and anticipating the range of specific conscious and unconscious responses to specific sensory inputs, as images, colors, textures, sounds, etc.

- Utilizing the communicative nature of movement and primal physiological gestures to affect and study specific mind-body states.

- Examining the capacity for the mind and senses to directly affect physiological response and biological change.

- In psychodynamic psychotherapy, clinicians utilize various psychodynamic theories of the unconscious, such as regression, to alleviate mental tensions in clients.[19]

- Cognitive psychodynamics is a blend of traditional psychodynamic concepts with cognitive psychology and neuroscience, resulting in a relatively accessible and sensible theory of mental structure and function.[20]

- In the 2003 book Mapping the Organizational Psyche – a Jungian Theory of Organizational Dynamics, psychologist John Corlett and author Carol Pearson develop a Jungian-style organizational psychodynamics allowing business leaders, in the midst of self-reflection and corporate restructuring, to “delve deeper into the corporate consciousness” so to better study the unconscious dynamics of organizational behavior in business.

See also

References

- ↑ Psychodynamics - McGraw-Hill Science Tech Dictionary

- ↑ What is psychodynamics? - WebMD, Stedman’s Medical Dictionary 28th Edition, Copyright© 2006_Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Bowlby, John (1999). Attachment and Loss: Vol I, 2nd Ed. Basic Books. pp. 13–23. ISBN 0-465-00543-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Freud, Sigmund (1923). The Ego and the Id. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. (4-5). ISBN 0-393-0042-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hall, Calvin, S. (1954). A Primer in Freudian Psychology. Meridian Book. ISBN 0452011833.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Psychodynamics (1874) - (1) the psychology of mental or emotional forces or processes developing especially in early childhood and their effects on behavior and mental states; (2) explanation ! or interpretation, as of behavior or mental states, in terms of mental or emotional forces or processes; (3) motivational forces acting especially at the unconscious level. Source: Merriam-Webster, 2000, CD-ROM, version 2.5

- ↑ Psychodynamics – Microsoft Encarta

- ↑ Robertson, Robin (1995). Chaos theory in Psychology and Life Sciences. LEA, Inc. pp. (83). ISBN 0805817379. Unknown parameter

|coauthors=ignored (help) - ↑ Klimek, David (1979). Beneath Mate Selection and Marriage - the Unconscious Motives in Human Pairing. Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 3. ISBN 0-442-23074-5.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ahles, Scott, R. (2004). Our Inner World: A Guide to Psychodynamics and Psychotherapy. John Hopkins University Press. pp. (1-2). ISBN 0801878365.

- ↑ Horowitz, Mardi, J. (1988). Introduction to Psychodynamics - a New Synthesis. Basic Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-465-03561-2.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Berne, Eric (1964). Games People Play – The Basic Hand Book of Transactional Analysis. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-41003-3.

- ↑ Walsh, Anthony (1991). The Science of Love - Understanding Love and its Effects on Mind and Body. Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87957-648-9. Text " pages 58" ignored (help)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hall, Calvin S.; Nordby, Vernon J. (1999). A Primer of Jungian Psychology. New York: Meridian. ISBN 0-452-01186-8.

- ↑ ibid page 80

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. (pgs. 4,6). New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-092043-2

- ↑ Marsh, Ann. (2005). “The Art of Work” Fast Company, Issue 97, August, pg. 76.

- ↑ Psychodynamics - an Introduction

- ↑ Psychodynamic psychotherapy - guidetopsychology.com

- ↑ Horowitz, Mardi, J. (2001). Cognitive Psychodynamics – from Conflict to Character. Wiley. ISBN 0471117722.

Further reading

- Brown, Junius Flagg & Menninger, Karl Augustus (1940). The Psychodynamics of Abnormal Behavior, 484 pages, McGraw-Hill Book Company, inc.

- Weiss, Edoardo (1950). Principles of Psychodynamics, 268 pages, Grune & Stratton

- Pearson Education (1970). The Psychodynamics of Patient Care Prentice Hall, 422 pgs. Standford Univerity: Higher Education Division.

- Jean Laplanche et J.B. Pontalis (1974). The Language of Psycho-Analysis, Editeur: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-01105-4

- Raphael-Leff, Joan (2005). Parent Infant Psychodynamics – Wild Things, Mirrors, and Ghosts. Wiley. ISBN 1-86156-346-9.